Background

A look back at the most important climate conferences since 1992

Annual climate summits have become an established feature on the international conference calendar. The meetings take place in a different country in the second part of each year. Parties to the UN Convention on Climate Change come together at these events to review and drive progress on climate change mitigation and adaptation through new resolutions. This year, the Conference of the Parties (CoP) will be meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. As this marks the 27th meeting, the event will be known as COP27. It all began in 1992. Let’s take a look back at the key milestones along the way.

1992, Rio de Janeiro: the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is approved

1992, Rio de Janeiro: the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is approved

As early as the 1970s, the scientific and academic community engaged in intensive discussions on the trend of rising air temperatures at various locations around the globe. But it was to take another 20 years or so before the global community adopted resolutions on the issue. In the early 1990s, the United Nations tasked representatives from 150 countries with drafting the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was opened for signature at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (also known as the Earth Summit) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. It bears this name because it served solely as a framework and did not contain any specific commitments for each state. The document generally refers to climate change as a ‘common concern of humankind’ and outlines the goal of preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. States should therefore reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 1990’s levels by the start of the new millennium.

1994: the Convention enters into force

The UNFCCC entered into force in 1994 after gathering the necessary number of at least 50 ratifications. The parties that have ratified the Convention, which now number 198, have since met annually at the now very well-known international climate change conferences.

1995, COP1, Berlin: the first COP

The first climate summit after the UNFCCC had entered into force was held in Berlin to flesh out its details. The Berlin Mandate was adopted to this end, formally opening negotiations on binding climate change agreements that culminated in an additional protocol (known as the Kyoto Protocol) two years later.

1997, COP3, Kyoto: the Kyoto Protocol is adopted

1997, COP3, Kyoto: the Kyoto Protocol is adopted

The third global climate change conference took place in Kyoto, Japan. An additional protocol of the same name was approved in Kyoto, which brought to life and further developed the UNFCCC. For the first time, it set binding targets under international law for greenhouse gas emissions in industrialised countries. In a first phase running until 2012, these countries were to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 5.2 per cent on average compared with 1990’s levels. However, it took seven years for the protocol to take effect because of its highly controversial nature. The US, for instance, was vigorously opposed to its provisions.

2000, COP6, The Hague: negotiations become gridlocked

The climate conference in The Hague was the first major defeat for global climate action. It ended without a final agreement. One point of contention was whether and what types of CO2 sinks – natural carbon reservoirs – could be included. The breakdown of negotiations led to a second part of COP 6, known as COP 6-2, being held in Bonn in the summer of the following year. Considerable progress was made at the event – without the US, which withdrew from the protocol under George W. Bush. The parties agreed on steps including complying with certain upper limits on the inclusion of sinks.

2005, COP11, Montreal: the Kyoto Protocol enters into force

The Kyoto Protocol entered into force after two conditions were met. First, it had to be ratified by 55 states. These states had to account for at least 55 per cent of total CO2 emissions from industrialised countries in 1990. These conditions were not met until early 2005; it took seven years for this to happen. At the climate summit in Montreal, the parties decided to extend the life of the Kyoto Protocol beyond 2012 and to start negotiations to this end.

2009, COP15, Copenhagen: climate diplomacy reaches a low point

2009, COP15, Copenhagen: climate diplomacy reaches a low point

The global climate change conference in Copenhagen is considered a low point in climate diplomacy. It ended with an empty political statement that was not adopted but only taken note of. In the accord, the parties to the contract recognised that global warming must be kept below 2 °C. However, it made no long-term arrangements going beyond 2012 and no binding commitments to reduce CO2 emissions.

2011, COP17, Durban: a new era begins

With the continuation of the Kyoto Protocol becoming an ever more distant prospect, the parties agreed to embark on a new negotiation process at the climate conference in Durban, which was to include all countries and not just industrialised states.

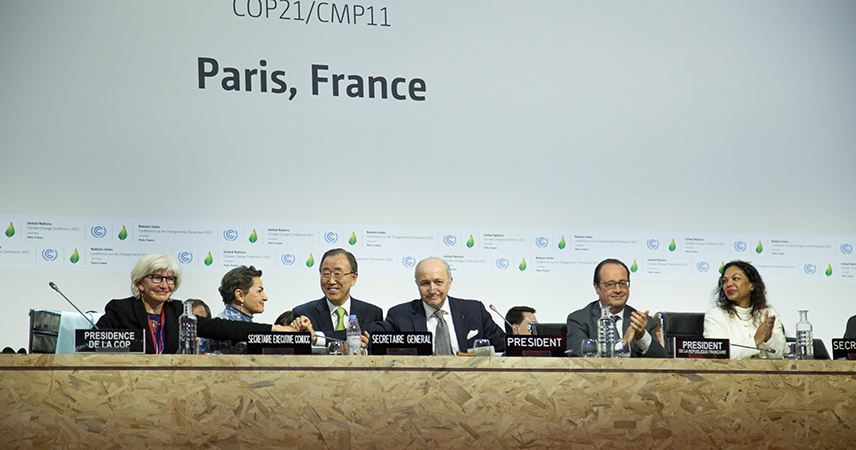

2015, COP21, Paris: the parties reach an agreement

2015, COP21, Paris: the parties reach an agreement

A breakthrough was reached in the French capital at COP21: the parties agreed on the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty that replaced the Kyoto Protocol. It states that global warming should be reduced to 2 °C, preferably to 1.5 °C. For the first time, it applied to all states without exception, including developing countries and emerging economies. Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement contains no fixed and agreed commitments to reduce greenhouse gases, but instead nationally determined contributions (NDCs). In these NDCs, states determine the contributions that they aim to make to climate change mitigation and submit their goals to the UNFCCC Secretariat. The sum of all submitted NDCs provides information about the path that the world is on to addressing global warming and how big the gap is to the 1.5 °C target.

2021, COP26, Glasgow: a break and then a reunion

2021, COP26, Glasgow: a break and then a reunion

Plans to gather in 2020 were cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The meeting was pushed back to the following year, to take place in Glasgow, Scotland in 2021. At the event, the parties to the Convention adopted the Glasgow Climate Pact, affirming their support for the 1.5-degree goal, among other things. The pact also calls for closing down coal-fired power plants and phasing out subsidies for fossil energy. Although specific dates were not given for either pledge, this reference was considered new and groundbreaking.

2022, COP27, Sharm El-Sheikh: meeting in the midst of an energy and food crisis

This year’s climate conference is taking place against the backdrop of a global energy and food crisis prompted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the related challenges. Nevertheless, the discussions will focus on the parties setting more ambitious national climate change mitigation goals, as the commitments made to date are not enough to keep global warming below 1.5 °C. The world is currently on track for global warming of around 2.5 °C. As the host and a representative of Africa, Egypt is making the issue of climate change adaptation a priority, as many African countries, in particular, are battling the impacts of climate change. And climate financing will also play an important role. In the Paris Agreement, industrialised states pledged to provide USD 100 billion each year to developing countries from 2020 onwards. This promise is still far from being upheld.

UN Climate Change Conference 2022: COP 27 at a glance (giz.de)

Global CO2 emissions: the warmest seven years on record (giz.de)

1.5 degree target: small difference, big impact | akzente (giz.de)

„Climate is part of our DNA“ by Jörg Linke, Head of GIZ’s Competence Centre for Climate Change

A village is saving its jungle | akzente (giz.de)

The woman putting solar panels on Gaza rooftops

A look back at climate conferences to date (in German; bundesregierung.de)

The history of climate change conferences, also known as COPs (lifegate.com)

History of the Convention – Essential background (unfccc.int)

History of the Convention – Climate Change in context (unfccc.int)

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – United Nations – Regional Information Centre for Western Europe (in German; unric.org)