The Green Climate Fund (GCF) provides financing for climate projects in developing countries – for both greenhouse gas reduction and climate change adaptation. This helps countries to implement the Paris Agreement. Germany is one of the most important donors to the fund. The forest conservation project in Lao PDR is one example of how a country is being supported in its efforts to protect valuable forests. The jungle provides a livelihood for the rural population. And every tree helps to sequester carbon, thereby reducing the amount of climate-damaging CO2 in the atmosphere.

A village is saving its jungle

Lao PDR’s tropical forests are a treasure. But they are under threat from slash-and-burn practices. We meet the people protecting the trees.

In sandals and a patterned skirt, Tong Yang walks through tropical forest in Lao PDR, her eyes scanning the undergrowth beside the loamy trail. The young woman carefully pushes a few branches to one side – in the hope of quickly revealing something for her evening meal. It’s the rainy period right now and that means: mushroom season. Shaded by tall Castanopsis trees, Tong Yang spots a promising red shimmer. Bullseye! She pulls several handfuls of mushrooms out of the ground. The 28-year-old says all she has to do now is decide whether to fry what she has harvested or make a soup with her spoils instead.

Easy access to fertile forests like those bordering Tong Yang’s community of Khangkhao is no longer a given in Lao PDR. Although the country with around seven million inhabitants has the highest proportion of land under forest cover on the South-East Asian mainland, the jungle area has shrunk considerably in recent decades. In the mid-1960s, 70 per cent of the national territory was still forested. Today, the figure is just 58 per cent and much of what is left has suffered significant damage.

Slash-and-burn practices linked to agricultural development are one of the main drivers of this decline – in Khangkhao, too, the bare patches have become bigger and bigger over recent years. Together with other villagers, Tong Yang wants to help to reverse this trend. ‘The forest provides us with fresh air, it provides us with food,’ she says while unearthing some roots that she can sell as traditional medicine at the market. ‘Obviously, we have to ensure that it is preserved.’

The people protecting the forest are being supported by a project being implemented in Lao PDR by GIZ on behalf of the German Development Ministry (BMZ) and with financial support from the Green Climate Fund. 240 communities are now working to make agriculture and forestry sustainable. The goal is to stop deforestation, thereby preventing millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions – while improving the living conditions of the local population at the same time.

Life in the region is not easy. Khangkhao is located in Houaphanh province, one of the country’s poorest areas. Tong Yang is a mother of five – she had her first child at just 18 years of age. She and her husband used to earn an income mainly from growing rice. But the family was barely making ends meet with the proceeds from this – and the nutrient-poor soils could only be relied on to deliver a harvest for a couple of years. Like many in the region, mainly engaged in dry rice cultivation on account of the hilly landscape, Tong Yang therefore had to regularly find new fields. This included clearing patches of forest herself to make space to grow her rice. But that’s in the past now.

The forest conservation project has helped her to create an alternative: with a black plastic bucket full of pig feed, Tong Yang walks the two kilometres to a slope where she used to grow her rice. The plot is now fenced in and is home to a small herd of cattle as well as chickens and pigs. Tong pours out the contents of a bag of cattle salt over a wooden board and is quickly surrounded by the cattle that now constitute her new livelihood. Along with others from the village, she has been trained by agricultural experts from GIZ and the local forestry authority on raising animals, on the medicines and vaccines they need and on how to plant grass for fodder. She says her income is now considerably higher from selling the mature animals than from when she grew rice. In good months, she can even put aside the equivalent of several hundred euros. The fact that Tong Yang is no longer forced to destroy the forest in order to clear land for new rice fields is a step in the right direction – for the farmer herself and for the environment.

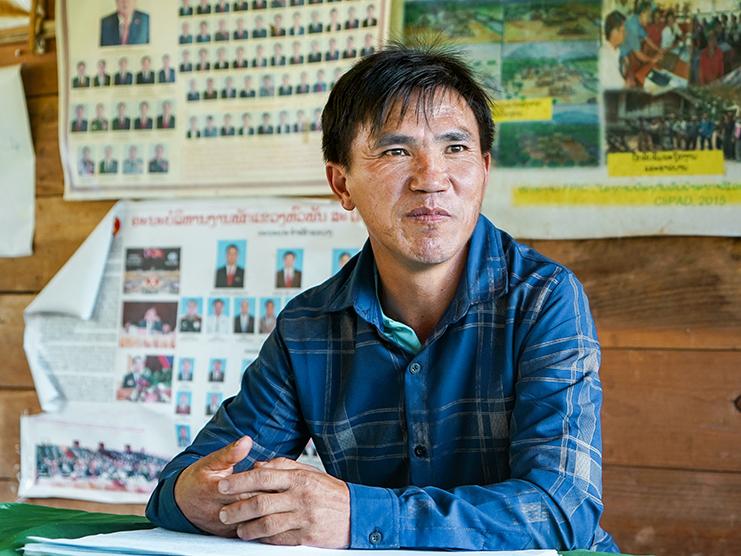

In her community, Tong Yang is now an active proponent of jungle conservation. She meets one Thursday morning with fellow campaigners in a wooden hut with a corrugated iron roof that serves as a community centre. Village leader Yerdongxai Nengyang has convened the gathering to take stock of the situation. Reading from a notebook with closely written text, he presents the key activities of recent months: forest management budget planning, forest fire prevention measures and patrols of the conservation area. He adds that there are problems with a neighbouring community that does not accept the forest boundaries. He states that this will have to be clarified now with the help of local authorities.

Clarity regarding who is responsible for which tracts of land and how the areas can be used is fundamental to the forest conservation project. A satellite image on an information board at the entrance to the village precisely delineates the forest boundaries – indicating where slash-and-burn practices are prohibited. The map was jointly drawn up by those living in the area and employees of the local forestry authority. The village community signed to confirm its commitment to comply.

Chueneng Yang is one of the men monitoring this. The 41-year-old is a member of the local forest committee. Twice a month, he and his colleagues undertake a patrol of the village forest – and report back if they discover illegal deforestation. ‘In two cases, the authorities are currently following up on the information we provided,’ he explains. However, it’s not always easy to find the culprits: the group often has to overnight in the forest during their patrols – sleeping on banana leaves on the ground. The forest protectors are remunerated for this work.

And their engagement is beneficial for their fellow villagers: if they can successfully protect their forest over a longer period, communities such as Khangkhao also get bonus payments that are earmarked for the village fund, enabling further investment in sustainable agriculture and forestry. The money can be used, for example, as start-up financing for the cultivation of agricultural products that can be easily brought to market and for which slash-and-burn practices are not required. Tea and coffee plants are popular in this regard, along with the creation of ponds for fish farming.

Farmer Tong Yang sees her future in livestock farming – and is hoping to further expand her small family business. She’d like to purchase more animals. ‘I’m working hard to give my children an easier future,’ she says.