stock.adobe.com/bob

stock.adobe.com/bob

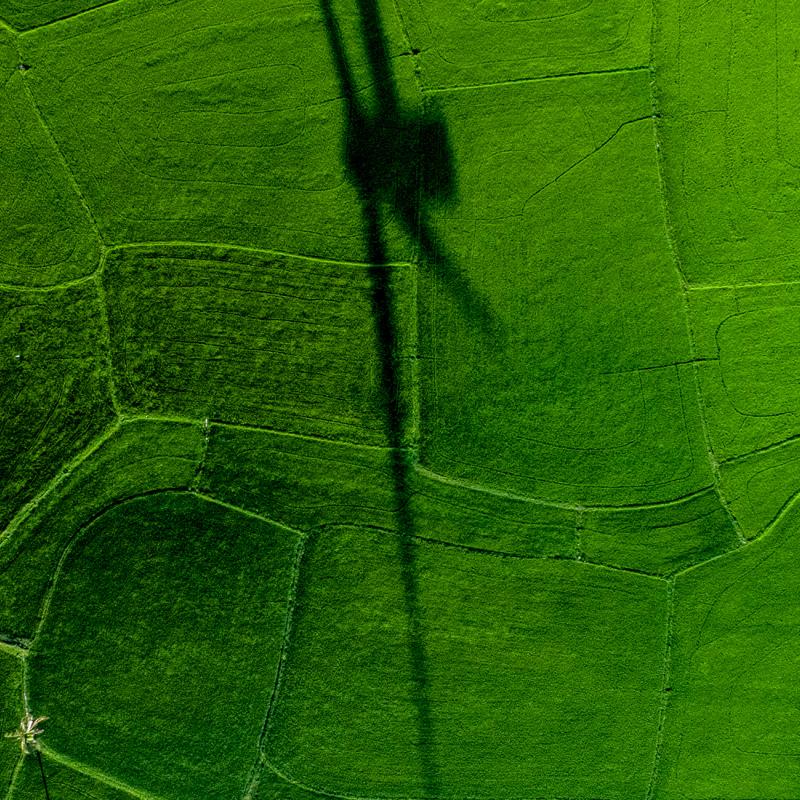

Methane, the underestimated danger

The focus of the climate change debate is shifting more towards the role of methane. Despite causing greater damage to the environment than carbon dioxide, the gas offers considerable potential in terms of emissions savings. As a ‘methane champion’, Germany is looking to lead by example.

Methane is a climate-impacting air pollutant which stems in large part from human activities. Fossil fuel use, agriculture and waste management are primary sources of methane emissions. Over a 20-year period, it is 86 times more potent at warming than carbon dioxide (CO2). Moreover, the gas has accounted for roughly 30 per cent of global warming since the start of the Industrial Revolution. Nevertheless, awareness of its impacts is growing only gradually. Compared with CO2, methane emissions can be cut quicker and more easily, and the reduction could trim approximately 0.3 degrees off the rise in temperatures.

Methane is also a contributor to the formation of ground-level ozone. Besides irritating the respiratory tract, this can trigger coughing and shortness of breath and is also associated with many other illnesses, such as cancer. It also impacts plant growth: exposure to ozone over a prolonged period can reduce harvest yields. Methane therefore not only warms the climate but also – through ozone – adversely affects humans and nature, is a cause of premature death and undermines food security.

Target: 30 per cent Methane reduction by 2030

The Global Methane Pledge was launched by the United States and the European Union (EU) at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) as a way of harnessing the potential savings in methane emissions for the benefit of climate change mitigation. The aim of countries signing up to the Pledge is to cut their methane emissions by at least 30 per cent by 2030. This initiative is now supported by 150 nations, including Germany as well as many developing countries and emerging economies, such as Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan and Viet Nam. These are among the largest methane emitters in the Global South and are also GIZ partner countries. Germany sees itself as leading the way in this field and was recently designated as a ‘methane champion’. This brings with it a commitment to support other countries in reducing their methane emissions and to take ambitious measures domestically.

For GIZ, besides working intensively on projects and programmes aimed at reducing CO2 emissions, this also means focusing increasingly on reducing methane emissions as part of international cooperation. Here are three examples:

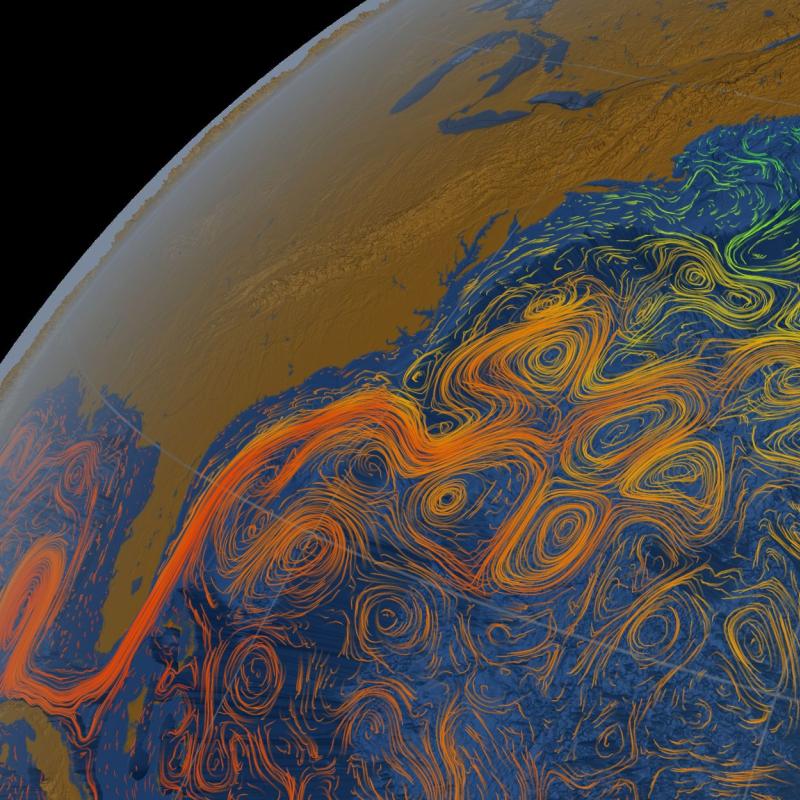

Rice cultivation in Thailand

Rice is a food staple in Thailand – and dominates agriculture in the country. However, wet-rice cultivation is harmful to the environment as the absence of oxygen in waterlogged soil allows microorganisms to thrive and decompose plant residues, creating methane in the process.

GIZ

GIZ

The government is therefore working together with partners such as GIZ to find ways of making rice cultivation more environmentally friendly. This is currently taking place in six provinces in Thailand under the Thai Rice NAMA (Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action) programme. Under this initiative, rice farmers learn about cultivation methods that produce fewer emissions, focusing essentially on alternate wetting and drying. Combined with fertilisation systems adapted to the local conditions, this practice can cut emissions by a minimum of 70 per cent.

By the end of 2023, the aim is for 100,000 Thai farmers to have reduced greenhouse gas emissions by around 1.7 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent. This is the same as the annual volume of CO2 emitted by roughly 260,000 Thais. In view of the success achieved to date, Thailand would now like to expand the programme to a total of 15 provinces.

Livestock farming in Africa

Animals such as cows, goats and sheep produce methane during the digestive process. It is then released into the atmosphere through belching and flatulence. Methane also escapes during the storage and application of manure and slurry. This is also a problem in Africa given that agriculture is the continent’s most important economic sector. Livestock farming accounts for around 70 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture.

FireFXStudio/stock.adobe.com

FireFXStudio/stock.adobe.com

It is now known that adapted feed and improvements in pasture and manure management are ways of reducing gas emissions. To familiarise farmers with such methods, GIZ has implemented the Programme for Climate-Smart Livestock Systems (PCSL) in cooperation with the International Livestock Research Institute and the World Bank.

The programme began in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda with the aim of conducting research into the most climate-friendly methods of livestock farming in the respective regions. This led to recommendations on husbandry and feeding practices. Training courses on climate-friendly methods were also given to 10,000 livestock farmers.

Building on the PCSL, GIZ is now designing a new global programme aimed at making climate-smart livestock systems more widespread in Africa.

Waste and wastewater management

The decomposition of organic components on rubbish dumps and the non-treatment or anaerobic treatment of wastewater with a high organic load are two ways in which methane is produced. This is why proper waste and wastewater management is also key to protecting the climate. However, this rarely occurs in developing countries where an estimated 90 per cent of all wastewater is discharged untreated into streams, rivers, lakes and oceans.

GIZ

GIZ

A project by the name of FELICITY therefore promoted low-emission projects in Brazil, Ecuador, Indonesia and Mexico. Modern sewage treatment facilities were set up at four sites in Ecuador, together with one waste processing plant in Mexico.

The FELICITY project ran from 2018 to 2022 in the four countries mentioned and in ten cities. Follow-on projects are in the pipeline, not least because the methane emissions from the waste sector continue to rise in many regions.