Report

Programmed for health

It is still early in the morning, but a long queue has already formed in front of Sarkari Karmachari Hospital (SKH) in Bangladesh’s sprawling capital Dhaka. Mothers and their coughing children, elderly people on crutches and young men swathed in bandages all wait impatiently. A few metres away, traffic thunders past. Amid all the hustle and bustle, 57-year-old dermatologist Dr Mohammed Ali Chowdhury radiates a sense of calm as he ushers one patient after another into his compact consulting room on the first floor. Although pressed for time, he wants to do the best he can for every patient. ‘There are not enough doctors to treat so many sick people,’ he explains, his voice calm. ‘But we are coping much better than we used to.’ He points to what has become one of his most important items of equipment: the computer.

Dr Chowdhury’s demanding working day is better organised than before because of the quiet revolution taking place in Bangladesh’s hospitals. The country’s national health system is being computerised, with GIZ’s support. ‘Digitalisation is making patient care quicker, cheaper and better,’ says Kelvin Hui, a GIZ expert who was responsible for introducing the digital systems that are transforming health care in Bangladesh. From 2012 to 2016, GIZ provided support for Bangladesh’s Ministry of Health in implementing the reforms. The project was commissioned by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The authorities in this South-East Asian country have now assumed ownership of the process and are driving it forward on an independent basis. GIZ’s experts have moved on to Nepal, where they are now setting up a country-wide health information platform designed on similar lines.

Next, please

So what has improved? Watch Dr Chowdhury at work for a while and it all becomes clear. His next patient is 56-year-old police officer Ali Hossain. A member of an elite unit, he is in uniform and greets the doctor with a click of his heels. He seems to be in good shape, but he has a skin irritation all over his body and is not fully fit for service.

„Previously, I would have had to spend time and effort finding out about the patient’s medical history. Now all it takes is a click of the mouse.“

Doctor Mohammed Ali Chowdhury

Officer Hossain has brought along a temporary patient identification card which was issued to him on previous visits to the hospital. Dr Chowdhury scans in the barcode and opens the patient’s digital file. A glance at the records tells him that a dermatologist is not the right specialist to be treating this patient: Hossain has diabetes. ‘Previously, I would have had to spend time and effort asking the right questions,’ says Dr Chowdhury. ‘Now all it takes is a click of the mouse.’

Prescribing the right medication

An experienced medical practitioner, he knows that diabetes is probably the cause of the problem. He sends Officer Hossain along the corridor to another specialist and then calls the next patient. ‘I see up to 30 patients a day,’ he says. ‘So every saved minute counts.’ And the patients are happy if they don’t have to wait for too long. ‘Today, I was seen after 20 minutes,’ says Ali Hossain. ‘On previous visits, I often had a much longer wait.’

Next door, there is more evidence that the electronic patient records are proving useful. Dr Jesmin Akhter is treating a young man with a skin rash on his scalp, which he is constantly scratching. With the aid of the database, it takes no time at all for her to check which drugs have already been prescribed. They are clearly not working, so she decides to try a different one. The electronic patient records also help to ensure that the patient is not prescribed the same medication by several different doctors.

Bangladesh is still one of the world’s poorest countries. Despite a sharp increase in average life expectancy to 72 years and a fall in child and maternal mortality, health care provision is still very basic. According to the World Bank, annual total health spending per capita is around USD 30 in Bangladesh. In Germany, it is more than USD 5,000.

Digitalisation is helping to improve the allocation of scarce resources. So far, 15,000 hospitals and smaller treatment centres have joined the Health Ministry network. They share data, including information on diagnoses and hospital bed occupancy. Previously, this information would have been collected using a pen and paper and would have taken weeks to reach the Ministry. And not only that: there were often gaps or inaccuracies in the datasets.

Fighting epidemics

With the new system, the civil servants now have much faster access to information, which is also useful when epidemics threaten to strike. In Bangladesh, dengue fever – a highly contagious viral infection spread by mosquitoes – comes in waves. A vaccine did not become available until 2015. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), dengue fever kills about 20,000 people a year. With the new system in place, doctors can quickly identify the regions where high numbers of people are infected, thus enabling a rapid response. The entire public health system, with its 105 million patients, benefits as a result.

The costs of the new technology are relatively low. At GIZ’s suggestion, it uses open source software – programs which are usually available free of charge. The source codes are made available to the public, allowing ongoing development of the software by universities, non-governmental organisations and volunteers. For hospitals, this cuts the costs of setting up an IT system by up to two thirds, according to Muhammad Abdul Hannan Khan, who previously worked on the project for GIZ and now manages it in his role as team leader for HISP Bangladesh, a non-governmental organisation.

Training for 20,000 doctors and nurses

Increasingly, hospitals are now using OpenMRS (Open Medical Record System) – developed by the University of Indiana and the US aid organisation Partners In Health – to manage their electronic patient records. DHIS 2 (District Health Information System), for which core development activities are coordinated by the University of Oslo, is used to connect the hospitals with the Ministry. The software is now in use in more than 30 countries, including India. In Nepal, GIZ is working with partners to replicate the digital success achieved in Bangladesh.

But it is not enough simply to download and install the software. GIZ’s experts and partners must first modify the programmes to meet the needs of the individual hospitals and health systems. In Bangladesh, for example, double occupancy of beds is common due to lack of capacity, and the programmers must adapt the basic software to take such aspects into account. The next step is to train the thousands of health workers to use the programmes. In Bangladesh, more than 20,000 doctors and nurses now have the skills they need to navigate the system.

„Over the long term, we want to set up a national patient information database.“

IT-Expert Abdul Hannan Khan

Inspired by these successes, Bangladesh is pressing ahead with digitalisation. Another aim is to improve inter-hospital communication. ‘Over the long term, we want to set up a national patient information database,’ says IT expert Muhammad Abdul Hannan Khan. ‘It will take years, though, so we’re just at the beginning.’

Little card – big impact

On the face of it, it’s just a little plastic card – but it has so much to offer. The health insurance schemes now being set up in many countries around the world ensure that illness or incapacity is no longer a poverty risk. In Nepal, for example, GIZ spent many years advising the Government on setting up a scheme and has also helped to establish similar systems in India, Indonesia, Rwanda and Kenya. Between 2010 and 2015, GIZ and its partners enabled more than 302 million people worldwide to gain improved access to insurance.

Examples of GIZ’s work – more facts and figures: www.giz.de/projectdata

Sarkari Karmachari Hospital sees itself as a pioneer in this process. Dr Chowdhury pulls out a patient ID card. It’s roughly the same size as a credit card. This one is just a prototype but soon, every patient will be given a card like this. It has a barcode that will enable other hospitals to access the patient’s records – a great help when someone is referred to a specialist at another clinic.

There are plans to computerise further areas within the hospital. The nurses at Sarkari Karmachari Hospital are not working with the electronic patient records yet, but that’s about to change, says Dr Chowdhury. And many of them won’t need training to use the system: working with the computer programmes is already part of the national curriculum for nursing education in Bangladesh.

published in akzente 1/18

The digital divide

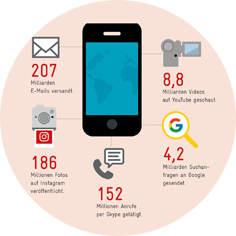

Infographic: Digitalisation

‘A tool for development’

Interview: Digitalisation