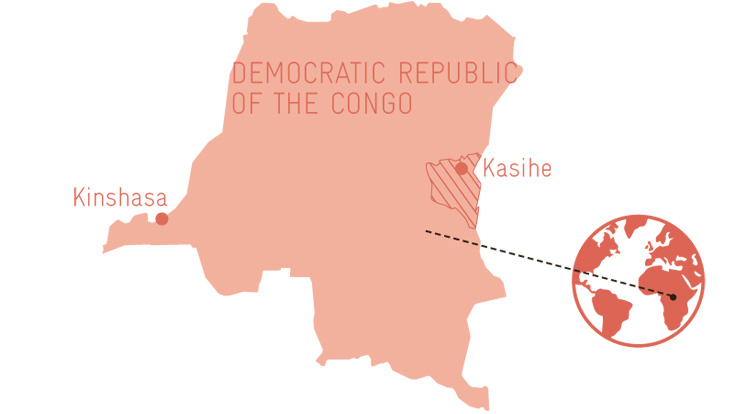

DR Congo

Healthy Future

Three-month-old Chishesa Zihindula contentedly sucks her fingers, oblivious to the hustle and bustle around her. Her mother Ester Zawadi Mwachigabo brought her youngest daughter to the health centre in the eastern Congolese community of Kasihe first thing this morning to be vaccinated against tuberculosis and diphtheria.

‘It is important to me that my daughter is well protected against diseases,’ says Zawadi, ‘and the vaccinations here are free, so there was no question about coming.’ Zawadi is not the only one to think like that. Because of the vaccination campaign, almost 90 women have come to the new health centre in Kasihe with their infants this morning. Kandanda Namuho, Head of the centre’s nursing staff, is quite proud of the big turn-out. ‘Our awareness-raising campaigns are clearly reaching the public, and people trust us,’ he says.

That’s not something that can be taken for granted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In some regions in the east of the country, barely a quarter of the population is treated in health centres or hospitals. Medical care is poor following years of neglect of the health system by the central government in Kinshasa. At the same time, many people cannot afford to pay for medical services, however inadequate. Moreover, staff often lack motivation, as the government effectively pays only 10 per cent of employees. The rest rely on the meagre and unreliable income generated by the facilities themselves.

To ensure that people in the Congolese province of South Kivu benefit from better medical care, GIZ is working on behalf of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in eight health zones in the region. The programme Supporting the Health Care System in South Kivu works closely with the province’s Ministry of Health, its health department and authorities. This will give 1.5 million people improved access to decentralised and dependable health services.

‘We are reaching the public and people trust us.’

Kandanda Namuho,Head of the nursing staff at Kasihe medical centre

The minister responsible for health care in the province, Vincent Cibanvunya Murhega, welcomes the assistance and knows that the situation urgently needs to change. ‘Child and maternal mortality in South Kivu are higher than anywhere else in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ he says. For every 1,000 newborns, 139 die in South Kivu. In Germany, it is just three. Over 40 per cent of the population of South Kivu is also undernourished, more than in any other part of the country. And the situation is critical nationwide. The United Nations Human Development Index ranks the Democratic Republic of the Congo 176th out of 189 countries – despite the fact that the country could theoretically be rich, given its fertile soils and wealth of raw materials such as coltan, an ore highly sought after by the computer industry.

Patients used to be treated in a mud hut

The extremely poor state of health in South Kivu can be attributed in part to the conflicts that have ravaged the mineral-rich province for almost 25 years. Dozens of militia are involved in fighting for control of valuable natural resources. For years, hundreds of thousands of people have been forcibly displaced time and again, cannot work their fields or subsist. Almost 85 per cent are classified as poor, meaning they have less than USD 1.90 per day to live on and almost no money for medical treatment. And the modest income generated by medical facilities is not put to proper use due to poor management. Plans are now in place to make the health care system more efficient. ‘We want to ensure that everyone in the province has access to medical treatment,’ says Minister of Health Cibanvunya.

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Capital: Kinshasa / Population: approx. 81 million / GDP per capita: USD 458 / Economic growth: 3.4 per cent / Human Development Index ranking: 176 (out of 189)

The health programme commissioned by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation is advancing medical care in South Kivu. It is working with 12 local organisations.

www.giz.de

Contact: Antonio Lozito, antonio.lozito@giz.de

In Kasihe, the situation has already improved dramatically since the programme started. Kandanda Namuho enjoys giving tours of ‘his’ health centre. The newly constructed and equipped facility has been up and running since January 2018. Every month, 16 to 20 babies are now born there and an average of 180 patients treated. ‘These figures would have been unthinkable in the old health centre,’ says Namuho. He leads the way to the old building nearby, coming to a halt in front of a small mud hut, the roof of which has already collapsed and been covered with a blue tarpaulin. Up until a few months ago, this was the region’s medical facility – delivery room, treatment room and consultation room, all rolled into one.

Because many health centres are in a similar state of disrepair or much too small, improving medical infrastructure is a key component of the health initiative. In total, six of these local facilities have been renovated or newly built in South Kivu. The programme works with a total of 123 health centres and eight hospitals.

Now that he can attend to his patients in a well-lit, solid building, Kandanda Namuho enjoys his work more. He also gets performance-based bonuses, which means he now has significantly more money to live on. Specifically, around USD 15 per month in bonuses in addition to the average of USD 25 he is paid in health centre income. He and his colleagues receive nothing from central government. ‘We used to have trouble concentrating on our work because of the constant money worries,’ explains the 32-year-old father.

Finances are a major concern for everyone. Recovering the costs of the medication and treatment provided is a huge problem for many facilities, including Kasihe health centre. Only one third of his patients pay in full immediately after treatment, says Namuho. The remaining 70 per cent pay late, only in part or not at all. In Kasihe and the surrounding area, three to four per cent of patients have health insurance. This may not seem much, but it is still slightly higher than the average for the province as a whole, which is just two per cent. ‘Many people have had bad experiences in the past and no longer trust insurance schemes,’ explains Antonio Lozito, Manager of the health programme. That’s why the programme is helping existing insurance providers to improve management and efficiency. A fee system is also being introduced to ensure that medical services are affordable and prices stable. This will include the use of generic drugs produced in a controlled environment.

Ester Zawadi Mwachigabo, who is waiting for her daughter to be vaccinated, needs no convincing of the benefits of health insurance. She and her nine children have been insured since 2016. ‘It’s not easy for us to earn the USD 55 a year needed for the insurance,’ she says. ‘But it’s worth it.’ One of her children had to have an operation last year that cost USD 150: her insurance company paid half. It also covered the bulk of the costs of her last two highly complicated deliveries. ‘I’m now less worried about the future,’ says Zawadi. Illness no longer inevitably spells financial ruin for her family.

published in akzente 4/18