Cultural heritage

Albanian treasures

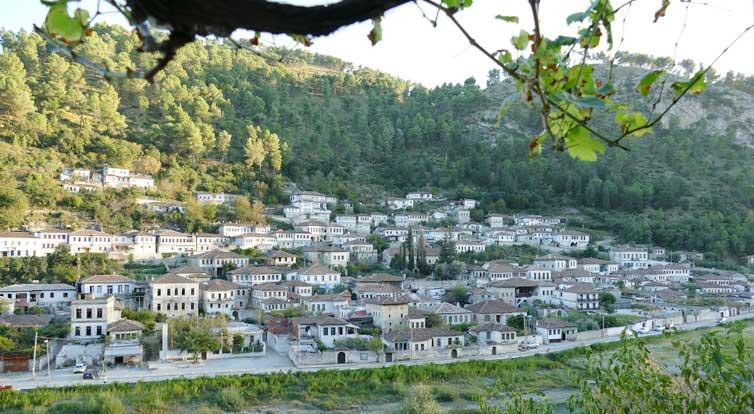

With a thud, the mixture of goat hair and lime lands on a 300-year-old wall. Majlinda Çuka concentrates as, standing atop some scaffolding, she uses a trowel to spread it thickly on to the underlying plaster. She is working on a historical treasure: along with other craft workers, Çuka is restoring one of Berat’s white houses. This central Albanian town, with its three compact old town quarters and numerous mosques and churches, is one of the country’s major tourist attractions. In 2008, Berat was awarded Unesco World Heritage status. The cobblestoned quarters with their old buildings and endless rows of windows are typical of the town.

In fact, Berat is known as ‘the town of the thousand windows’ for this reason and was declared a living museum by the former Albanian regime under Enver Hoxha. Back then, specialised skilled craft workers worked in ‘ateliers’ to take care of selected historical sites. However, after the fall of Communism in 1990 and during the difficult transition period that followed, this testimony to the country’s past fell into disregard. Albania’s young democracy faced many other problems and is still grappling with issues such as corruption and youth unemployment.

It’s not just about old stones

Precious stone buildings fell into disrepair, the master craftspeople leading the restoration lost their – hitherto highly prestigious – jobs, and commercial interests gained the upper hand. Yet it is especially important to preserve a country’s cultural heritage during uncertain times, argues Lejla Hadžić from Cultural Heritage without Borders Albania (CHWB).

This non-governmental organisation is dedicated to conserving historical sites and working for peace on the Balkan peninsula and is also active in other countries in the region.

On behalf of the German federal state of Hesse, GIZ has been supporting CHWB since 2016 in a skills development project in Albania. Around 130 craft workers have so far received training as specialist plasterers, carpenters and stonemasons. Around a quarter of them are Albanians who had fled their home country but have now returned. Certificates for the restoration courses provide written proof of their special skills in working on historical sites.

Restoration of these sites brings people from diverse backgrounds into contact with one another and also conveys a sense of security. ‘Cultural heritage is all around us: it has shaped us and made us what we are. When it disappears, that’s very unsettling,’ says Lejla Hadžić. The organisation also seeks to preserve the expertise of the master craftspeople and to pass it on to the next generations, giving them career prospects in their home country.

Experienced master craftspeople like Jorgji Fani from Berat are providing the training. Fani has been working on historical buildings for 45 years. A trained stonemason, he has also accumulated wide-ranging expertise in other fields. Fani is now instructing Majlinda Çuka, one of the small number of women in the restoration team. The 46-year-old has qualifications in painting frescoes and icons but found she could not afford to keep herself and her two children from the casual work she was finding in painting icons. So she decided to acquire further skills as a stucco plasterer and timber expert in Berat – despite living around 100 kilometres away in the capital, Tirana. Every morning, she catches the bus to Berat at 6:10. And when she gets home at 17:00, she starts her second job, working in the library of the large Orthodox cathedral in Tirana.

Çuka concedes that it’s a heavy workload, but says ‘with the additional skills I now have and my certificate, I have better prospects of finding work, including on frescoes.’ And she enjoys working with ‘Master Jorgji’ and her colleagues. While she is plastering the wall in the oldest part of the building, carpenters are sawing and hammering next door as they work on an ornate wooden ceiling.

On the ground floor, white limestone tiles have already been laid and are now being grouted. Everyone is working together to make the building – a ruin just a few months ago – into an architectural gem. When tourists wandering the old streets of Berat occasionally peer behind the white stone walls, the craft workers are proud of what they are achieving. And their hope is that their work will pay off for the whole town.

October 2018

Contacts:

Martina Ebensen, martina.ebensen@giz.de

Lejla Hadzic, lejla.hadzic@chwb.org