In the Sundarbans, GIZ combines the protection of biodiversity with efforts to strengthen livelihoods. The project Support to the Management of the Sundarbans Mangrove Forests in Bangladesh and the follow-on project are funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Political support is provided by the Bangladesh Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change and the country’s Forest Department. The Forest Department’s Sundarbans rangers have received training to use the innovative SMART management instrument. With this they can collect, store and analyse data on biodiversity and patrol routes, as well as violations of conservation laws. The teams have also been equipped with the requisite digital devices.

Custodians of the Sundarbans

In the world’s biggest mangrove forest, Bangladesh Forest Department rangers are focusing on preserving biodiversity. Digital tools are helping them to protect this UNESCO World Heritage Site. Germany is supporting the country in this work.

The small group moves vigilantly through the dense green foliage. The men put one foot in front of the other, looking left and right, listening for any noise. In the distance, there is a cracking sound in the undergrowth. One of the men looks through his binoculars. The rangers must remain alert at all times as this is the territory of the Bengal tiger.

Every day, Robiul Islam and his team patrol the Chandpai range, a conservation area for the Bengal tiger in the Sundarbans. The immense mangrove forests on the Bay of Bengal are still home to several hundred of these rare animals. Nowhere else in the world do these big cats live in mangrove areas.

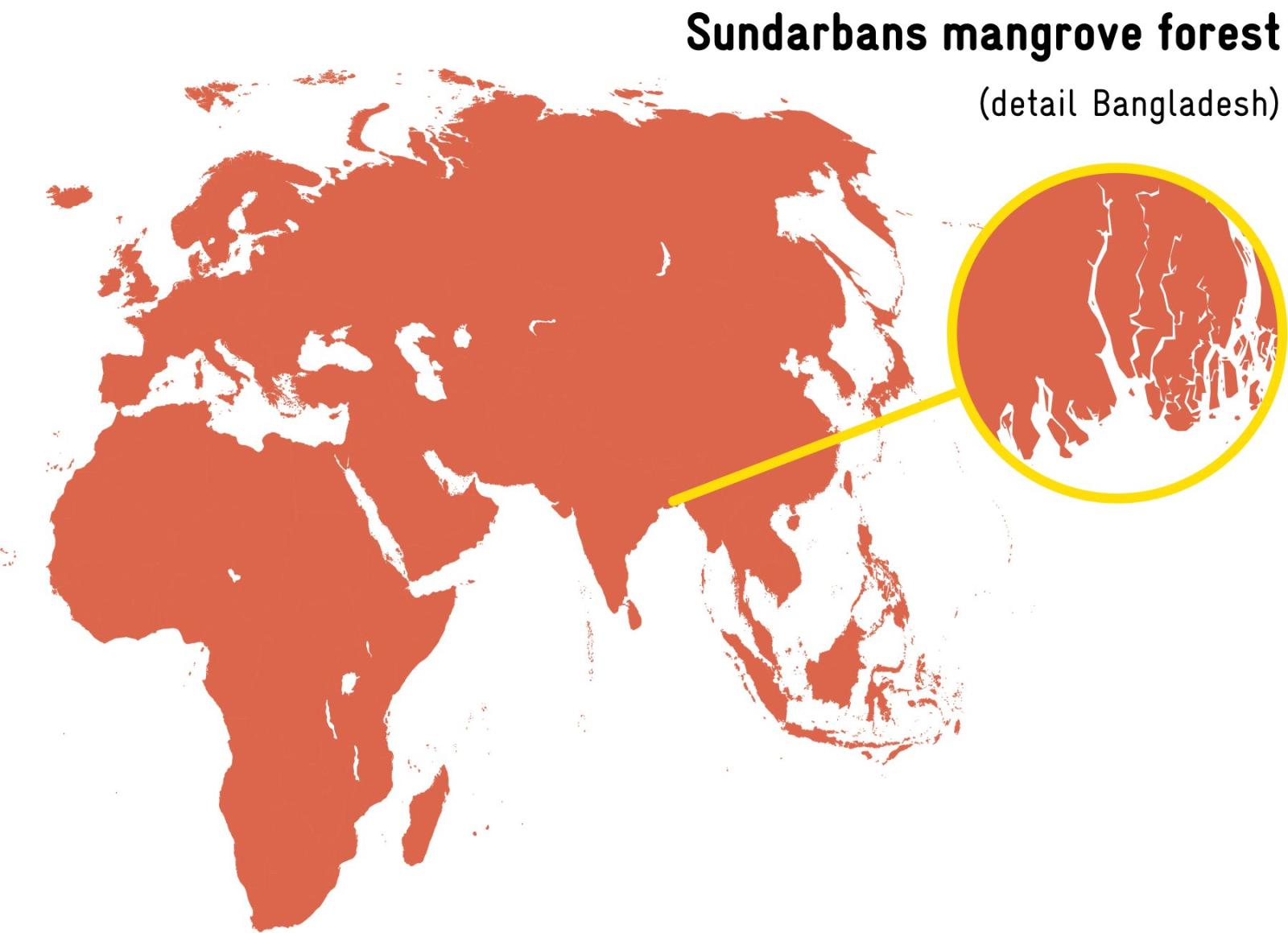

The ‘beautiful forest’, the literal meaning of Sundarbans, covers countless islands. Rivers and channels flow between the mangroves, a habitat unique to Bangladesh and neighbouring India. Covering some 10,000 square kilometres, the forest as a whole is almost as big as Jamaica. According to UNESCO, the mangroves of the Sundarbans form one of the most biologically productive ecosystems in the world.

This diverse archipelago at the boundary between freshwater and seawater provides a home for many rare plants and animals. The northern river terrapin, for instance, whose scientific name is Batagur baska. Forest Department rangers raise this endangered terrapin species at the Karamjal Wildlife Breeding Centre.

Robiul Islam manages the Dhansagar Forest Station in the heart of the Sundarbans, around 20 kilometres away from his colleagues in Karamjal, as the crow flies. His remit is twofold: to protect the forest’s treasures, namely the animals and plants, and to grant controlled access to people who depend on its resources for their survival. For example, the station manager issues fishing permits, because for many of those who live here – a poor region in one of the poorest countries in the world – fishing is the most important source of income.

The forestry officer must also ensure that tourist groups behave appropriately. ‘Everyone who visits the Sundarbans has to stick to the rules. It’s our country’s treasure and nobody’s private property.’

His team patrols the boundaries of the protected zone, checking, for instance, if loggers or trappers have entered unlawfully, for which fines would be imposed. This morning, they don’t find anyone who shouldn’t be there. ‘Behaviour has changed significantly in recent years thanks to increased awareness and knowledge,’ says Robiul Islam. The involvement of the local village communities has also helped with this, as described in the report ‘My neighbour, the Sundarbans World Heritage Site’.

Manager of the Dhansagar Forest Station, Robiul Islam, at his desk

Conserving biodiversity with smartphones and drones

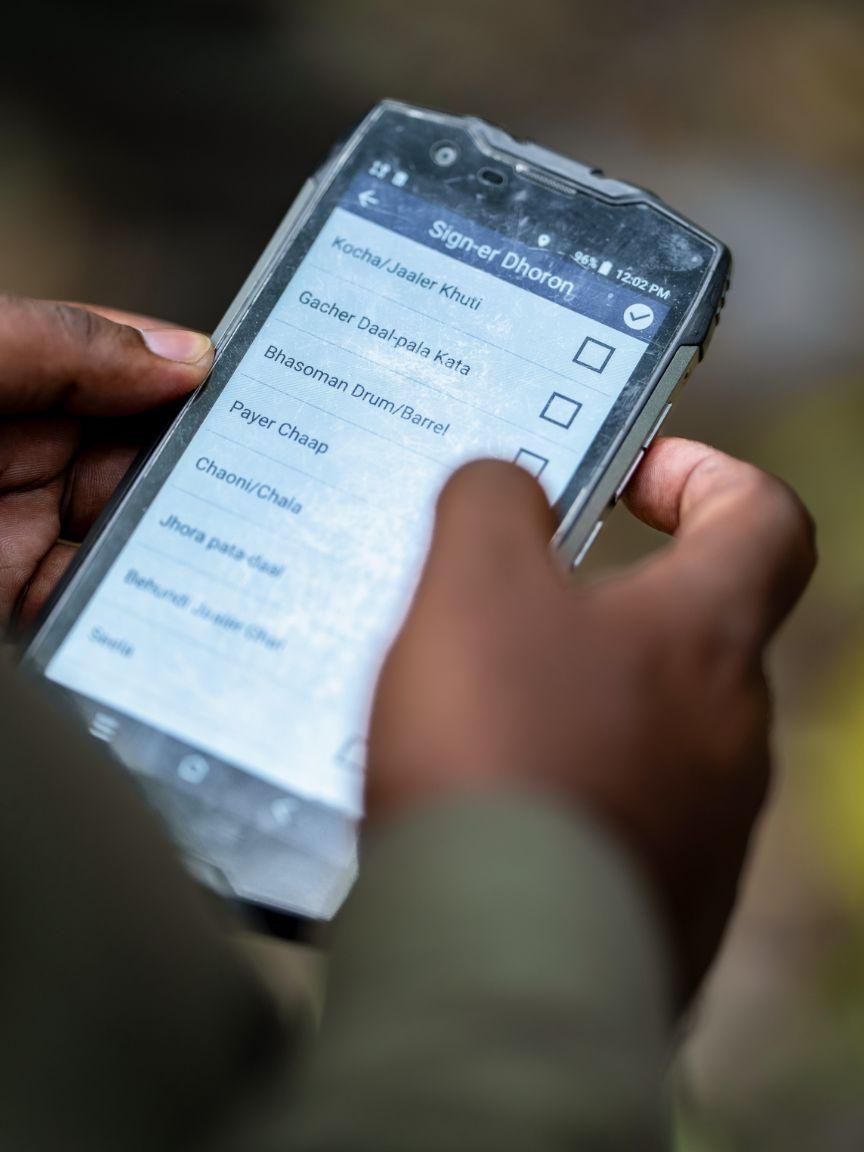

The forest rangers patrol in the mornings and afternoons. Some of them are responsible for security and carry guns. The rest of the team for the patrol consists of the station manager, animal observers and data collectors. In the past, all observations were noted by hand. Today, the rangers are equipped with smartphones with which they can record their observations immediately and include the related GPS data. This is all part of an ecological monitoring platform called Spatial Monitoring And Reporting Tools (SMART). These internationally recognised nature conservation instruments were introduced by the Bangladesh Forest Department in cooperation with the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

‘We can now accurately record our discoveries, add photos and pinpoint locations,’ explains Robiul Islam. ‘The data is reviewed and then sent to the Forest Department in Dhaka.’

The Dhansagar station manager is also a master trainer. Having completed training in the use of the SMART system himself, he now passes this knowledge on to his colleagues. ‘I was one of the first 16 to have the training. Since then we’ve shared what we learned with other colleagues in the field and with staff at the Forest Department.’ He is now so used to working with these digital tools that he couldn’t imagine the job without them.

Other equipment used includes drones flown by six trained pilots. These are especially important in the narrow water channels between the islands of the Sundarbans. ‘Even with small boats, we can’t get to those places, but using the drones we can still monitor the remote corners. That’s a real benefit of these smart tools,’ explains Robiul Islam.

This morning, the rangers are patrolling by conventional means – on foot. They find axis deer tracks and a print in the ground that they cannot immediately identify. Everything is photographed and recorded on a smartphone. Four hours later, they return to the station and their tension slowly abates. They will go out again later in the day – and they never know if there will be a Bengal tiger waiting for them in the Sundarbans.