In the Sundarbans, GIZ combines the protection of biodiversity with efforts to strengthen livelihoods and involves local people in the conservation of the vast mangrove forest. The project Support to the Management of the Sundarbans Mangrove Forests in Bangladesh and the follow-on project are funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Political support is provided by the Bangladesh Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change and the country’s Forest Department. During the COVID-19 pandemic, communities adjacent to the Sundarbans benefited from targeted food support and new education programmes for children.

‘My neighbour, the Sundarbans World Heritage Site’

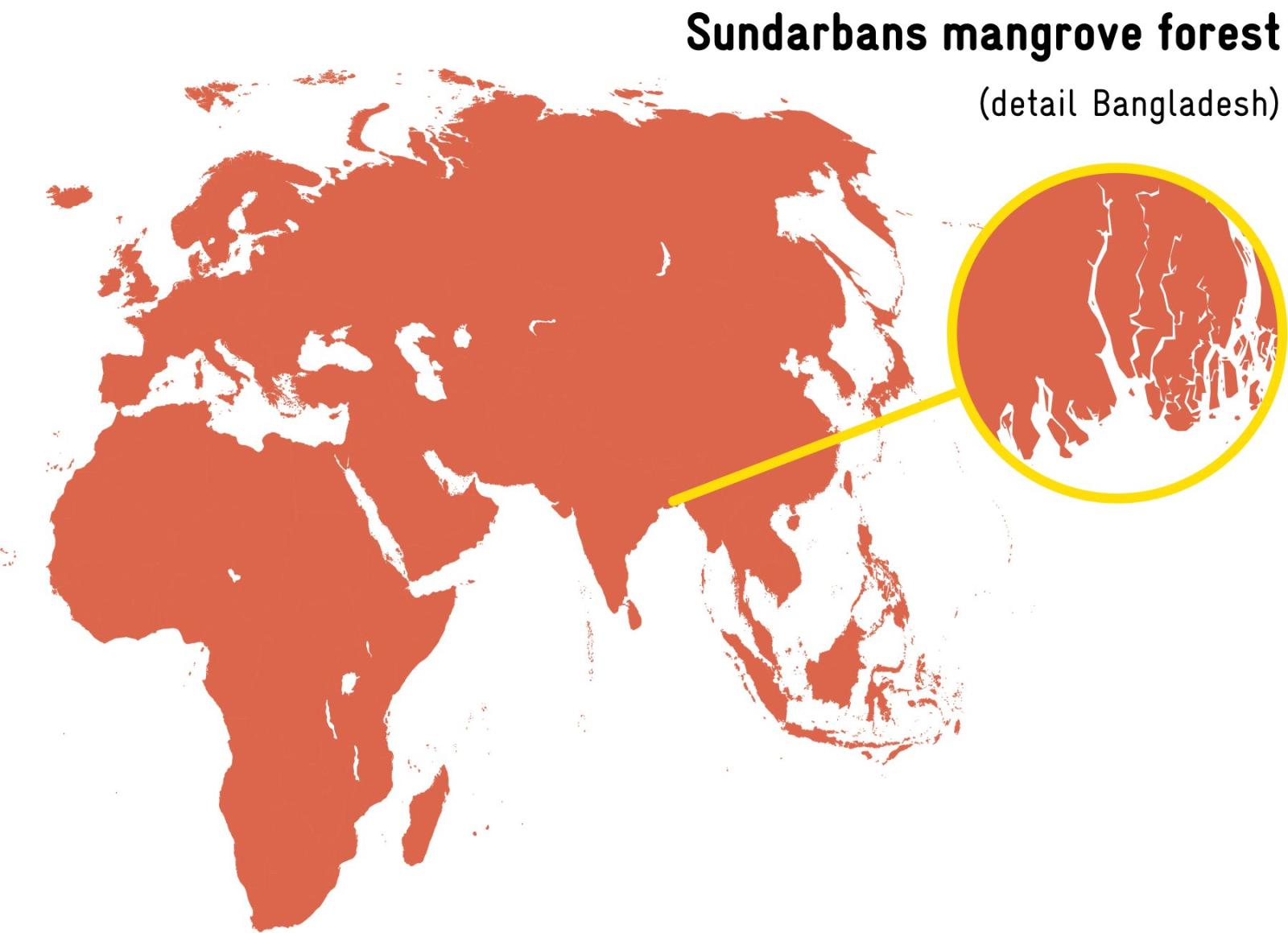

The world’s biggest mangrove forest is situated on the border between Bangladesh and India. We meet the people who live with and earn a livelihood from the Sundarbans UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Bodhomari is the place Rehana Begum calls home. The village lies on the edge of the Sundarbans, which means ‘beautiful forest’ in Bengali. Here, along the coast of Bangladesh and India, lies the largest mangrove forest in the world – a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Begum has spent over 30 years steering her boat around the delta in the south-west of Bangladesh, through the maze of channels and small islands shaped by the Ganges and other rivers.

Every six hours, vast quantities of water rise and fall here on the Bay of Bengal. The alternating ebb and flow of fresh water and seawater has created a fascinating ecosystem. The Sundarbans is among the last habitats of the endangered Bengal tiger, endangered river dolphins and many other animal and plant species, making it a treasure trove of biodiversity.

The mangrove belt also provides effective coastal protection, fending off the worst impacts of tropical storms and tsunamis. The mangroves’ interwoven root system prevents the soil from being washed away.

Life-giving Sundarbans

The Sundarbans provides a livelihood for more than 3.5 million people living in villages on the periphery of the protected area. People like Rehana Begum, who even as a child used to accompany her parents when they went fishing and crabbing. In those days, there was no school she could have attended, says Begum, now 40.

Fishing and the harvesting of wood and honey were the most important and often the only sources of income – as they still are today in this impoverished region of one of the world’s poorest countries.

Rehana Begum has lived in Bodhomari since she was born and can remember how people often used to catch fish using poison. They would pour pesticides into the water and the paralysed fish would float to the surface, where people gathered them up. ‘It didn’t occur to us that using toxic chemicals pollutes the rivers and ponds, and kills other animals,’ Begum says. Precious forests were also cleared. ‘We destroyed large areas of forest to fuel our stoves or to trade the wood.’

A new awareness for the UNESCO World Heritage Site

For some years now, Rehana Begum has witnessed a shift in attitudes and behaviour, both in herself and in others. She is now a member of a women’s group as well as a village conservation forum. Since 2015, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH has been working with local partners to get people involved in protecting the mangrove ecosystem. Workshops and training sessions have looked at ways to benefit from nature without destroying it. Women in particular have received support in playing a greater role in their communities. These activities have reached around 35,000 households and over 2,000 women.

For seven years now, Rehana Begum and her husband have been fishing without chemicals. And they no longer take wood from the Sundarbans to cook with, mostly using gas that they buy in canisters from the local bazaar instead. Otherwise they use wood from trees in the immediate vicinity of their house. The Begum family grows vegetables in front of their home and keeps cows, goats and chickens. This covers their own food needs and still leaves them some surplus to sell. This is an important factor for residents such as the Begum family: ‘The involvement of the local forest authorities and other groups makes it easier for us to find different ways of earning money.’

Contact with the Forest Department has improved overall, says Rehana Begum. ‘Now, if we see any wild animals in or near our village, we inform the Department so that they can catch them and return them to the forest.’

Her activities have inspired her brother, who now works as a volunteer with the community patrol group in the area. He helps preserve the forest by going on patrol with employees of the Forest Department to protect trees and wildlife.

Rehana Begum has not only developed a different approach to nature. Since becoming actively involved in the village community her self-confidence has grown. She has learned to write her name and to read the Qur’an. ‘I used to be too helpless and vulnerable to have any dreams. The women here would work their whole lives with their husbands, but were never given a share of the income or family decision-making. That has changed now.’

Her husband Khaleq Hawlader, who has been listening, nods. He was won over by his wife’s sense of purpose after she attended the workshops and courses. He encouraged her efforts to learn more, and he appreciates the fact that she now teaches children in the neighbourhood to recite the Qur’an and even earns some money from doing so.

Sharing knowledge with the next generation

‘When we were illiterate and could only live off the forest, we couldn’t imagine doing any other kind of work,’ says Begum. ‘The more knowledge I acquired, the more important it was for me to help my youngest daughter Lamia and my granddaughters Sumaiya and Mariyam to get educated.’ Every day, Lamia (13) and Sumaiya (10) walk three kilometres to the nearest public school. At just two years old, Mariyam is still too young, but she will also benefit from her grandmother’s knowledge in the future. ‘I teach them everything I’ve learned from the project,’ says Begum. ‘I share my knowledge and hope that everyone understands how important it is to preserve the treasures of the forest.’