Essay Human Security

Two steps forward, one step back

IN THIS ARTICLE

1. PAST

How the concept of human security emerged and took root.

2. PRESENT

Which developments threaten the world and therefore undermine human security.

3. FUTURE

Five points which the global community should address in order to promote human development.

With the Cold War ending, the exclusive focus on state security vanished, and the wellbeing of individuals came to the fore. Only a few years into this ‘New World Order’, the United Nations Development Programme introduced a new paradigm – Human Security – in its annual Human Development Report (HDR). The UNDP warned that ‘without the promotion of people-centred development none of our key objectives can be met – not peace, not human rights, not environmental protection, not reduced population growth, not social integration. It is far cheaper and far more humane to act early and to act upstream than to pick up the pieces downstream …’ Built on four principles – people-centred, comprehensive, context-sensitive, preventive – the new Human Security approach was preceded by a shift in development economics. The Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq and the Indian Nobel laureate Amartya Sen introduced an approach that switched from national income accounting to people-centred politics. ‘People are the real wealth of a nation,’ Haq wrote in the first Human Development Report in 1990. Hence, human development needed to become ‘a process of enlarging people’s choices’ – most critically about how to lead a long and healthy life, how to be educated and how to enjoy a decent standard of living. Without ‘political freedom, guaranteed human rights and self-respect,’ Haq insisted, ‘all foreign aid would be in vain.’

Freedom and dignity

Despite this forceful, forward-looking paradigm shift, it took the United Nations General Assembly almost two decades to come up with a definition of human security that was accepted by all member states. The 2012 General Assembly Resolution on Human Security stresses the role of ‘Member States in identifying and addressing widespread and cross-cutting challenges to the survival, livelihood and dignity of their people’. Central to the approach is the idea that people have ‘the right to live in freedom and dignity, free from poverty and despair … with an equal opportunity to enjoy all their rights and fully develop their human potential’.

But the debate on human security was not only led by the development aid community; it was soon dominated and superposed by security events. With the decline of inter-state wars, atrocities committed within states attracted much more attention than during earlier decades of the twentieth century. Triggered by the genocides in Bosnia and Rwanda, the UN, supported by NATO, developed the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (R2P) doctrine, which gradually evolved and was eventually adopted in 2005, stating that the international community has a right – and the obligation – to intervene in sovereign states if they do not protect their citizens’ lives and wellbeing.

‘There is less public interest in helping others, even as globalisation has made us more interdependent.’

Even though this concept has been highly criticised as a pretext for military intervention and led to doubtful results in Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, the combination of these three new paradigms – human development, human security and R2P – now constitutes what is being discussed under the label of ‘comprehensive approach’. Without this paradigm shift, neither the Millennium Development Goals nor the Sustainable Development Goals could have been established as universal blueprints for the advancement of humanity and the protection of our habitat.

Upsides and downsides of globalisation

But all these paradigm shifts would have been empty promises without another big global driver: globalisation. Triggered by the end of the bipolar order, the next wave of globalisation boosted the free flow of people, capital, data, ideas and goods on a much greater scale than the earlier waves of global interdependence between 1860 and 1914 and after the Second World War. The newly created World Trade Organization (WTO) encouraged all nations to embrace free trade, and in 2001 even China, a developing state, became a member.

‘Between 1990 and 2010, the proportion of people living on less than two US dollars a day fell to around 10 per cent.’

At the same time, the Fourth Industrial Revolution, prompted by digitalisation and the internet, connected people across the world at almost zero marginal cost, allowing for a deeper integration of global value chains. Saving on labour costs, western companies shifted more production to emerging-market countries. As a result of this boost to growth in the developing world, a new middle-class grew up, further fuelling economic expansion.

‘The result,’ as the World Economic Forum once dubbed it, ‘has been a globalisation on steroids.’ In the 2000s, global exports rose to about a quarter of global GDP and two-way or overall trade grew to about half of world GDP.

A rising middle class

he vast majority of the global population benefited from these developments: over the past 25 years, the socio-economic situation of large sections of the population in developing and emerging countries has improved considerably. Between 1990 and 2010‚ while the proportion of people living on less than two US dollars a day fell to around 10 per cent, the proportion of people from developing and emerging countries who belong to the global middle class tripled.

The rise of a global middle class is a story of epic proportions, contributing greatly to human security. More and more individuals can realise their potential, no longer trapped in a day-to-day struggle to survive. Still, the big gains for the middle class were concentrated in China, South America and Eastern Europe, and many in the global middle class worry about falling back into poverty as economic growth slows in a number of emerging markets. While the middle class expanded globally, in the West it saw its household incomes stagnate or decline, fuelling the current

populist sentiment, and thus increasing inequality and reducing human security.

Education is key

he increasing levels of educational attainment are perhaps the most positive sign of permanent change for the better. Educational attainment in the developing world is rising faster than it did for the West in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Young girls, not just boys, are benefiting. It is projected that the average number of years in education for women in the Middle East and North Africa could rise from five to seven years by 2030, which begins to close the gap with boys, who will go from 7.1 to 8.7 years in the same period.

‘To overcome the current nationalist backlash and cooperate with one another, governments need to shift away from their reactive crisis management mode.’

So, if we take stock of the progress achieved during the last 25 years, there has been real advancement. The World Bank estimated that the first Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of halving the proportion of people living on less than one US dollar a day was achieved in 2008, mainly due to progress in China, India and East Asia. Looking to the future, though, the most recent UN Global Sustainable Development Report in July 2019 warned that none of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals will be reached until 2030 if there is not a more concerted global effort.

The danger of climate change

After hundreds of years of imperialism, hegemony and conflict we should welcome the fact that we now live in a world of greater economic opportunity, individual empowerment, including that of women, and decreasing war. But with the rise of populist parties in Western countries and nationalism everywhere, democracy is in retreat and authoritarians are gaining ground. There is less public interest in helping others, even as globalisation has made us more interdependent. As the late UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan once put it: ‘Ours is a world in which no individual, and no country, exists in isolation. Pollution, organised crime and the proliferation of deadly weapons likewise show little regard for the niceties of borders; they are problems without passports and, as such, our common enemy.’

The biggest human security challenge requiring collective action is climate change. Those living in the sun belt, north and south of the equator, are most at risk. Sub-Saharan Africa – which could see the biggest impacts – is also where population growth is still surging. Hardly able to feed itself now, the expected increases in temperature will make it difficult to grow existing crops. The climate change threat is more widespread, with no country likely to be spared. Still, gaining international agreement on measures has been difficult. Advanced economies believe developing countries should bear more of the burden for cutting back CO2, while developing countries blame the West for the problem.

Shift away from reactive mode

To overcome the current nationalist backlash and cooperate with one another, governments need to shift away from their reactive crisis management mode. If political leaders want to reinvigorate the 2030 Agenda and deliver on their promise to improve human security, they need to better understand the fundamental drivers of change in our highly dynamic world. Only then will they be able to develop and implement policies relevant for solving challenges over the long term. Otherwise they will face a severe legitimacy gap and mistrust in institutions. This creates a fertile breeding ground for new social movements like Fridays For Future and eventually puts the political system under even more pressure. It is therefore all the more important to act swiftly and prudently. Not everything demands systemic change on a big scale; there are also low-hanging fruits:

First and foremost, political decision-makers and bureaucracies need to better understand the systemic interdependencies of a world that is becoming increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous.

Second, honest and straightforward communication with constituencies about the societal and individual costs of the desperately needed green socio-economic transition is indispensable. Policy-makers need to address vested interests if they want to achieve collective action.

Third, politics needs to become solution-focused instead of problem-oriented. It is not what people need to give up that should be in the centre of political communication but what could be gained.

Fourth, better coordination and harmonisation of sectoral policies (whole-of-government approach) and new forms of political participation, decision-making and shared responsibility are needed. Interministerial cooperation can be easily enhanced within national governments without constitutional changes.

Fifth, alignment with like-minded people – nationally as well as internationally – to demonstrate that change is possible.

Human development based on the principle of human security – i.e. a life free from fear and want for all races, genders and nationalities – will only be achieved if we reinvent our societies and political processes and understand that the welfare of others is just as necessary as our own. —

published in akzente 3/19

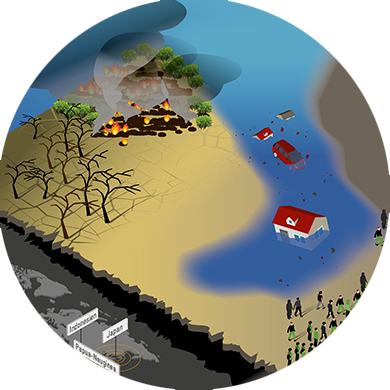

The biggest risks of all

Infographic Human security

‘It’s not just wrong, it’s stupid’

Interview Human security