Essay employment

New ways to tackle the global jobs crisis

We often think of a job as a source of income for workers. But jobs represent much more for society and individuals. Countries grow, for instance, when more people work, when each job in the economy becomes more productive, and when people move from low to higher productivity jobs. A good portion of the reduction in poverty that we have seen worldwide can be explained by an increase in the labour income of the poor, their main source of income. Jobs also contribute to the accumulation of human capital and promote social stability. A young person who is employed learns on the job, gains experience, makes other workers in the economy more productive and is less likely to engage in risky or criminal behaviour. Women who work also tend to invest more in the human capital of their children. Ultimately, our jobs give us a sense of identity, affect our level of wellbeing and determine whether we feel self-fulfilled or alienated, whether we are likely to start or join a revolution, and whether or not we vote and for whom.

IN THIS ARTICLE

1. More than a job

Why employment is so important for individuals and society.

2. Real dangers

How the difficult situation on the global labour market could get even worse.

3. What to do?

How targeted investments can create suitable jobs.

And yet, as important as jobs are, we are failing to avert a global crisis possibly as consequential as climate change. Indeed, a world in the not too distant future in which the majority of people do not work or are underemployed is now a real possibility. It is unlikely, however, to be a world in which people are happier, enjoying more leisure and time with their friends and families thanks to machines that take care of most tasks and generous government benefits (financed by the owners of the machines). At least at first, it could be a world of high inequality, social instability, widespread mental health problems, environmental degradation, and massive movements of people across borders.

‘Differences in job opportunities and earnings within and across countries are becoming more and more pronounced.’

Today there are roughly 7.5 billion human beings on planet Earth, 4.5 billion of whom are old enough but not too old to work. Of this number, 1.2 billion are inactive; they are not attending school, working, or looking for a job. According to World Bank calculations, 200 million of those classified as active are actually unemployed and 2 billion are underemployed. They are working just a few hours a week, are self-employed as subsistence farmers or in small household enterprises with very low productivity, selling products in tiny local markets. In Africa and South Asia, over 75 per cent of these workers do not produce or earn enough to feed their families; they are poor. In fact, the differences in job opportunities and earnings within and across countries are becoming more and more pronounced. This is creating social dislocation and is leading to massive movements of people. There are currently over 260 million international migrants (up from 170 million in 2000) and many millions of refugees. They are willing to cross borders and oceans, but receiving countries or regions are not always ready for them. Those who survive the journey often face destitution, abuse or exploitation.

New technologies will continue to displace jobs

Demographics and technological change will complicate things further. In countries in Africa and South Asia with young populations, there will be many new entrants to the labour market. It is estimated that middle and low-income countries will need to create 530 million jobs by 2030 to absorb them, yet at the current pace they may create only 400 million. At the same time, in high-income countries where populations are getting older, the challenge is to get people to work for longer in order to keep afloat strained social security systems. This is not easy to do, particularly in the face of fast technological change. New technologies are displacing – and will continue to displace – jobs not only on the factory floor but also in the services sector. From accountants and travel agents to paralegals and soon drivers. Granted, new technologies also open up opportunities to create new products and services and therefore new jobs. But it is not easy for those who had the old jobs to take on the new ones; the skills and competencies are very different. More than that, new jobs are likely to be created in very different sectors and in faraway regions.

We economists got things wrong. We had too much faith in the idea that, as long as countries put in place the ‘right’ business environment – meaning the right macro and regulatory policies – private investments would increase, resources would flow to the most productive sectors and regions, economies would grow and jobs would follow. To address the jobs challenge, it was therefore thought that countries needed to promote macroeconomic stability, simplify business regulations, promote investments in infrastructure and education, and improve governance. But as important as these policies are, they are insufficient.

Growth does not automatically mean new jobs

First, even with stability and the right business environment, private investments do not happen on the scale needed if there is not enough entrepreneurial capacity, which is often the case in developing countries. More importantly, in situations in which countries need to achieve social objectives through employment, it is unlikely that private entrepreneurs or investors alone can generate the right number and distribution of jobs. This is what we have seen even in countries such as Georgia and Chile, which have been prolific with the adoption of structural reforms. The data shows, in fact, that many growth episodes across countries have taken place with little to show in terms of job creation or without addressing issues related to poverty, the informal sector, youth unemployment and low female labour force participation. The sectors and regions in which investments are made – usually urban areas with the right infrastructure – are not necessarily where vulnerable workers live. Moreover, they are not usually the sectors that demand the skills they have.

So what should we do? We need to start thinking about jobs the way we think about carbon emissions. We know that carbon emissions contribute to global warming and are therefore bad for society. We also know that the private sector is not really paying attention to the social costs of the emissions it generates as a result of its investments and production decisions. This is why governments try to tax carbon emissions and/or subsidise the development of technologies that reduce emissions. With jobs, we need to do something similar. Objectively speaking, the function of the private sector is not to create jobs or address the social problems that emerge because of a lack of good jobs. Entrepreneurs, investors and managers do great things for society, but what drives them in most cases are financial returns, not jobs. Because they do not take into account the social consequences that their investments and production decisions have on jobs, governments need to intervene by subsidising the creation of certain jobs and taxing the destruction of others.

So what should we do? We need to start thinking about jobs the way we think about carbon emissions. We know that carbon emissions contribute to global warming and are therefore bad for society. We also know that the private sector is not really paying attention to the social costs of the emissions it generates as a result of its investments and production decisions. This is why governments try to tax carbon emissions and/or subsidise the development of technologies that reduce emissions. With jobs, we need to do something similar. Objectively speaking, the function of the private sector is not to create jobs or address the social problems that emerge because of a lack of good jobs. Entrepreneurs, investors and managers do great things for society, but what drives them in most cases are financial returns, not jobs. Because they do not take into account the social consequences that their investments and production decisions have on jobs, governments need to intervene by subsidising the creation of certain jobs and taxing the destruction of others.

‘We had too much faith in the idea that, as long as countries put in place the ‘right’ business environment, private investments would increase.’

This is not referring to wage subsidies. Many countries have adopted programmes that try to reduce the cost of labour – for instance, by reducing social security contributions. Tunisia, for example, did so after the revolution, as have many other countries, including Chile, Jordan, and South Africa, as part of initiatives to promote youth employment. These programmes, however, have had a limited impact. This is in part because, when there is not enough productive capacity, adding labour, even if it is free, is not profitable.

Instead I am referring to programmes that subsidise private investments contingent on job creation or improvements in the quality of jobs for specific population groups in targeted regions. In a way, these programmes would resemble the ‘industrial policies’ successfully adopted by countries in East Asia. South Korea, for instance, introduced policies to develop technological capabilities, promote exports and build the domestic capacity to manufacture a range of intermediate goods such as plastics and steel. Support for particular industries and imports of the necessary foreign technology took several forms including subsidised capital, public investments in education (particularly engineering and science) and public infrastructure to facilitate technological transfers.

The focus then was on economic growth, but similar strategies can apply to jobs. The idea is not to pick winners but, instead, to recognise that certain private investments which are good for jobs might not take place because private rates of return are not high enough. For instance, investments in agriculture and agribusinesses in lagging, low-income or conflict regions that would create jobs for the poor or improve the quality of their current jobs might not materialise because investors can achieve higher returns elsewhere – for instance, in the stock market. Yet, due to jobs externalities, the social rate of return on investments in the agricultural sector can be quite high. In these cases, governments need to increase private rates of return on investments through direct or indirect subsidies. These can take the form of matching grants for private investments, public investments in basic infrastructure and social services, support for the development of value chains or technical assistance for start-ups or small and medium-sized enterprises.

The proposal: a fund for more jobs

Taxing job destruction is also not as crazy as it sounds. Many countries do it implicitly through labour regulations that restrict dismissals and require the payment of severance to workers who lose their jobs. But current policies discourage innovation, can harm the competitiveness of firms and eventually reduce job creation without necessarily offering good protection to workers. The proposal, instead, is to let firms manage their human resources as needed, and then replace severance pay (paid by employers) with unemployment insurance (paid by the government) and introduce a modest, explicit dismissal tax. The revenue generated by this tax would flow into a fund that could be used to finance active programmes that help workers connect to jobs or move from low to high-quality jobs.

Thus, as new technologies change the demand for different types of skills, an infrastructure would be in place to retrain workers and facilitate transitions to new jobs. Almost all countries have these programmes, which include different types of training, counselling, intermediation, job search assistance and mobility premiums. Unfortunately, only one third of the programmes that have been rigorously evaluated have had a positive impact. We need to improve the design of these programmes by adopting modern identification and statistical profiling systems to assess the main constraints facing beneficiaries, introducing rigorous monitoring and evaluations systems, and outsourcing the provision of an integrated package of services to providers (public and private) that are paid on the basis of results.

‘We need to start thinking about jobs the way we think about carbon emissions. Because entrepreneurs do not take into account the social consequences that their investments have on jobs, governments need to intervene with subsidies and taxes.’

Countries like South Korea, Malaysia, Colombia, Chile and more recently Tunisia are moving in this direction. To expand the coverage of these programmes, particularly to rural areas and vulnerable population groups, it is also necessary to rethink financing mechanisms. Thus far, programmes have been mainly financed through general revenues. However, many of the beneficiaries could finance at least part of the cost. For instance, a recent survey of young people in Nairobi, Kenya, showed that they would be willing to pay up to 50 per cent of the costs incurred.

Clearly, none of the reforms discussed above are easy to implement, and not all countries have the fiscal space to do so overnight. International organisations and bilateral donors will have an important role to play in facilitating reforms. Firstly, by trying as much as possible, to come up with a unified policy framework. Different organisations often have very different diagnostics and offer very different policy recommendations, which is not particularly helpful for the country. Secondly, by mobilising the necessary technical expertise, including data collection, monitoring and evaluation systems. And thirdly, by adjusting their portfolio of lending, investments and grant operations. Today a considerable amount of resources are allocated to activities and projects which are supposed to focus on jobs but in practice do not. Developing new instruments and models to support lending and investments for jobs is key. Finally, as in the case of the East Asian Tigers, it is imperative that governments get their act together. A leaner and better prepared civil service can go a long way to improving policy-making and the allocation of public expenditure, in consultation with social partners.

published in akzente 3/18

Learning for life

Employment

A long way to go

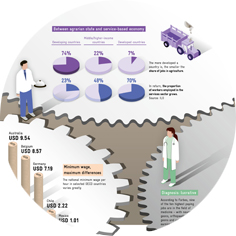

Infographic employment

‘Africa is on the rise’

Interview employment