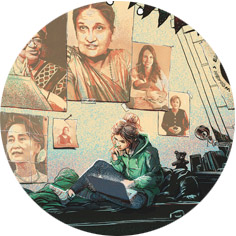

Interview women

‘Don’t try to be superwomen’

Around the world, more and more women are being appointed to high political offices. Where are we in terms of equal power-sharing?

That’s true! More and more women are being appointed to political office, and what’s even more inspiring is that many of them are young women, some from underrepresented groups of society. This is, in part, what makes healthy democracies. In terms of equal power-sharing, I like to make an analogy to football, which is very popular in my country: leaving women out of society is like playing a game with half of the team, that team is always at a disadvantage.

What could and should be done to support this trend?

During my term in office and in order to reduce gender disparity, we created the Ministry of Women and Gender Equality, providing the necessary relevance and resources to solve a myriad of gender-related issues. Until last year, the presence and participation of women in the two chambers of Congress was just 16 per cent, a reality that changed thanks to the Quota Law that was approved in January 2015. That allowed us to ensure that at least 40 per cent of candidates for Congress were women. And we also created incentives similar to those in the Quota Act to enable women to join public and private business directorates.

Does that mean that women are now on an equal footing?

It is still a struggle to be a woman in politics, even though very few people today would dare to question our capacity to do the same things. There is still a cost associated with the way in which we are evaluated in the exercise of public office. This happened to me in Chile, but it also occurs around the world; just look at what happened during the last presidential campaign in the United States and some of the sexist comments about Hillary Clinton. For women, the personal costs are high, we spend less time with our families and our lives are overexposed. We have to read and listen to comments about our physical appearance and are confronted with lies about many different topics. Nonetheless, these costs are nothing in comparison with the satisfaction of seeing how you can help improve people’s lives. When I was President and I visited my country’s regions or different neighbourhoods, and so many people thanked us: that was priceless. And it definitely makes it worth it.

When women are in power, do they govern differently?

I have always said that, if one woman enters politics, the woman changes. If many women enter, politics change. In Chile, for example, we have had a female president of the Senate, female presidents of political parties and trade unions and female leaders in education in recent years, and they have shown that women can perform their duties in an excellent manner and in all areas of society. Having achieved that, we have dispelled myths and prejudices, expanded the horizon of opportunities for Chileans, and I also believe that we have motivated many women to get involved in politics and other decision-making spaces, working together for gender equality.

Are these personal impressions?

Yes, but they are also backed by statistics. In recent years we have seen positive changes in our societies. For example, Chileans today value masculine and feminine leadership in the same way, as shown by a recent UNDP report. Less than a decade ago, 38 per cent of citizens still believed that men were better political leaders than women, but today almost 80 per cent of the population disagrees with that statement. I think this is an important cultural shift that allows us to be optimistic about the future of our countries in terms of equity, justice and progress.

I believe that, although there is still a lot to do with regard to equality and the empowerment of women in politics and leadership roles in general, society’s vision is advancing. It is understood that women in power do not necessarily have to act like men to carry out their work. It is still necessary to make greater efforts for validation, of course, but it is increasingly clear that power cannot and should not be the exclusive realm of men, and that today it is not necessary to be a man in order to be a political leader.

Are female politicians generally more social and less corrupt – or is that just a positive prejudice?

I honestly don’t know if that is true, but I suspect it is what you call a ‘positive prejudice’. Some of the most common stereotypes are that women are less selfish, more charitable and altruistic or that, being mothers, they have stronger values. Having said that, I did once read a report which said that in democracies, where corruption tends to be stigmatised to a higher degree than in other forms of government, women disapprove of corruption more than men, and are less likely to engage in corrupt practices.

I imagine that the premise behind this concept is that, because there are more men in higher positions of power, we see more prominent corruption cases associated with men in the media. However, even if there was evidence that women are intrinsically less corrupt than men, increasing women’s participation is still a desirable policy choice. Even if it did not reduce corruption directly, it would contribute to gender equality.

Are women in public office judged according to the same criteria as their male counterparts?

I have always worked, by choice, in the public sphere, and I continuously see clear biases against women. Women are often analysed according to criteria that are not even relevant. For example, a Danish prime minister once told me that, during her campaign, the press was more interested in analysing the size of her handbag than the content of the agenda she was trying to set. The same thing happens in my country. When I was a minister, a male colleague of mine who was on the ‘bigger’ side was known as ‘Panzer’, a word synonymous with power. Meanwhile, a ‘big’ woman is simply considered big. As President, I also went through this. Evaluations and criticisms of women are different in tone and form than those of men.

But what’s most dramatic is that this criticism also comes from women themselves. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, for example, where I was participating as the Executive Director of UN Women, I met with businesswomen and many of them did not have a gender perspective. They said: ‘I am where I am because I am good at my job, not because I am a woman.’ And I answered: ‘I was President of Chile because I am good at my job – almost despite being a woman.’ But because I am a woman and know that there are many competent women out there, I do everything possible to enable many more of them, with their skills and talents, to access areas where they deserve to be and can make a difference.

Having been elected President of Chile twice is, of course, a result of my hard work. Although it was not something I necessarily planned, I was prepared to work in the public sphere. I was interested in collaborating to improve people’s lives, especially with the most vulnerable groups in society. I overcame the same barriers that most women do. The difference is that my process was public knowledge. That is why I do not feel special or anointed in any way.

Some people fear that the rise of populism could be a step backwards in terms of women and political power. How do you feel about that?

Well, I come from a country that went through a great deal to regain its freedom and democracy after 17 years of dictatorship. And like my compatriots and millions of other people all over the world, I know that the task is not over once democracy is achieved. In the ongoing task of building a democracy, we cannot let our guard down, and the resurgence of populism is definitely an issue that should concern us. In that sense, my experience has unquestionably made me conscious of the frailty of democratic institutions, but also of the importance of civil society, including women’s groups, in the fight for the return of democracy.

However, women have always participated in political life – whether in Chile during the 1980s or during the Arab Spring just a few years ago. So no, I believe that if we, the international community, continue to work towards gender equality, politically empowering women through measures such as quota laws, women will continue to spearhead the important advances our societies need.

What ‘golden advice’ would you give young women looking to enter politics?

Don’t try to be superwomen or supergirls, because it will only lead to frustration. Instead, seek the help of someone you can count on. Be assertive, but also learn the art of dialogue, learn to communicate. Also, do not let your guard down; keep your eyes and ears open. Listen, look, but above all, act when necessary, with courage and generosity. That is politics: a permanent work in progress, in which women must participate. And, of course you should always try to keep your sense of humour!

published in akzente 4/18

The rise of women

Essay Women