Essay

Green and fair

In Lima it is hard not to spot Edgar Fernández. Among the countless vans and trucks jostling through the streets of Peru’s capital in a cloud of exhaust fumes, the young coffee roaster uses a yellow zero emissions cargo bike to transport his wares, some 70 kilos of raw coffee beans. Once the beans have been roasted, he jumps back on his bike to deliver the finished product to his customers. The pandemic struck Peru with great ferocity and continues to wreak havoc. Yet even in the toughest moments, Edgar’s business boomed. He was able to continue delivering coffee directly even when the shops were closed. Looking ahead, he will have to fight off the competition again, but this is a business model with a bright future. The beans come from small local farms. In fact, Edgar’s business brings together many of those key elements that we need to embrace, including sustainability, environmental conservation and fairness.

The international community can only achieve its goal of limiting human-induced global warming to a tolerable level if we reshape our economies in ways that no longer damage our climate, create social injustice or ruthlessly exploit the natural world. Strangely enough, it is the deadly COVID-19 pandemic that has given us an opportunity to make that change. Two words now form the great rallying cry of our times: ‘green recovery’. All our efforts to rebuild economic systems weakened by the pandemic can and must be directed towards a social and environmental transformation. The message from UN Secretary-General António Guterres and many others is that this reboot can produce a healthier and more resilient world.

IN THIS ARTICLE

1. THE GOAL

Why the opportunity has now arisen to create a greener and more resilient world.

2. THE OBSTACLES

How and why we can all have a say in deciding whether to seize this moment or let it slip away.

3. THE PATH

How we can build economies back greener, even in developing countries.

We already have the blueprint in the form of the 2030 Agenda, a series of sustainable development targets defined by the international community and to be achieved by the end of this decade. The basic message was development and progress for all, but not at the expense of the environment and the climate. To date, global efforts to meet those targets have lacked ambition. Despite international agreements designed to limit the damage to our climate, CO₂ emissions rose by over 60 per cent between 1990 and 2017.

As stipulated under international law in the Paris Agreement, we need to cut our CO₂ emissions to net zero by 2050. That will require a rapid and far-reaching transition. The momentum created by the pandemic gives us a unique opportunity to embark on this path. Never before has so much money been directed all at once in pursuit of a single goal. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), however, less than a third of the spending commitments announced to date have had a positive impact on the climate and the environment. That is alarming. The recovery packages and programmes designed to inject life back into our economies should be used to drive the shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy, to develop resource-efficient technologies for our industries, skilled trades and agriculture, to promote environmentally sound building methods and to roll out climate-friendly infrastructure.

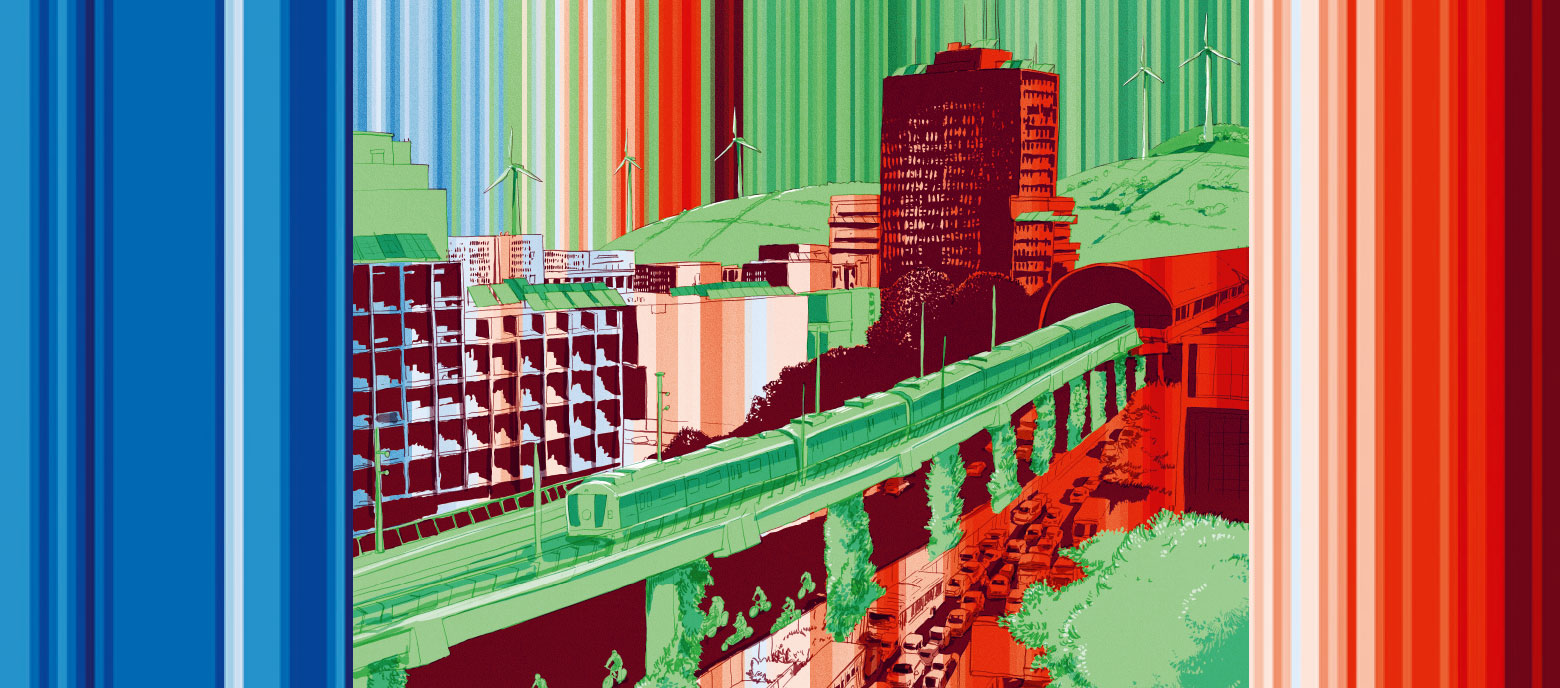

A green reboot along these lines could generate so many new jobs, especially in those developing countries where the pandemic has destroyed much of the progress achieved in recent years. India has shown how this can be done. Delhi’s metro system dates back to 2002. Work to extend it as part of the city’s wider public transport infrastructure created nearly 15,000 jobs. The project also generated employment on the production side as most of the trains and other technical rail systems are manufactured within the country.

‘The success of this transition depends on consumers all over the world rethinking their behaviour and making more sustainable choices.’

In Peru, the mayor of Lima wants to use international funding for climate action in urban areas to reduce air pollution in the capital. The plans involve building a series of ‘green islands’, planting two million new urban trees and creating 46 kilometres of cycle paths to help protect the climate and improve the quality of life for all of the city’s residents. This could also generate employment, for example building and maintaining all those green spaces and setting up new climate-friendly delivery services such as that provided by coffee-roasting entrepreneur Edgar Fernández. ‘If cities can find inclusive ways of tackling the climate crisis, they can act as a catalyst for economic recovery,’ observed the city’s mayor, Jorge Muñoz Wells.

Over in Rio’s Copacabana district, around 11,000 deliveries are already being made every day by cargo bike. In Mumbai, a major online retailer had the idea of using the traditional ‘dabbawala’ system, which provides many of the city’s office workers with a home-cooked lunch, to deliver parcels. Examples such as these show that even relatively small initiatives can set change in motion – and that even those on very modest incomes can benefit from the resulting changes.

The crucial role of agriculture

Yet if we are to achieve a wider global transition that allows the world’s leading economies to phase out fossil fuels completely, we need to lay correspondingly strong foundations. That is not yet the case, even though renewables have long since been competitive. In this context, however, it is worth noting that China, for example, now invests more in expanding its renewables capacity than in new coal-fired power stations.

One of the ‘elephants in the room’, as Peter Poschen from the University of Freiburg puts it, is agriculture. Agriculture is the second-biggest source of climate-damaging gases after energy. It also accounts for 70 per cent of worldwide water consumption and is one of the main drivers of another phenomenon, namely species loss. The expansion of agricultural land is a major contributing factor to deforestation and to the destruction of other plant and animal habitats. At the same time, however, agriculture is the biggest source of employment around the world. It is still by far the largest sector of the economy in developing countries. That means it has to be right at the centre of any plans for an economic reboot in the global south, especially since growing conditions have worsened considerably in many countries due to the climate crisis.

Making more sustainable choices

It is crucial that developing countries receive the funds they need to initiate a shift towards resource-efficient, climate-proof and socially equitable agricultural systems and economies that hold out the promise of a secure livelihood for their respective populations. In turn, this will require rapid action on debt relief and carefully targeted funding programmes. In some places, the transition has already begun. In western Uganda, for example, thousands of farmers have switched to cultivating organic crops, allowing them not only to generate more income but also to reduce their impact on the environment.

The success of this transition depends on consumers all over the world rethinking their behaviour and making more sustainable choices. In Lima, at least, Edgar Fernández’s customers seem to have understood that message.

published in akzente 3/21