GIZ is committed to supporting technical and vocational education and training around the world that prepares people for the green labour market. In Namibia, for example, GIZ is developing short training courses in green hydrogen, wind power and solar energy on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the European Union (EU). The project also has a focus on improving governance structures and training for trainers, as well as better adapting TVET and further training programmes to the needs of the labour market.

Max Bosse

Max Bosse

All eyes on Lüderitz

Green hydrogen is set to bring prosperity to Namibia and propel the world towards a climate-neutral economy. We travel to the country’s south-west, where plans are under way for one of the world’s largest hydrogen plants.

For Phillipus Balhao, the ghost town of Kolmanskop serves as both a warning and an incentive. Once Africa’s diamond boom town of the early 20th century, Kolmanskop now stands surrounded by desert, its buildings abandoned and sand strewn. For once the fields had yielded up their precious stones, the settlement fell into disrepair.

Balhao is the Mayor of Lüderitz. The port in the south of Namibia is just 10 kilometres from Kolmanskop. Everybody here is keen to avoid the mistakes of the past. ‘We want to be a role model,’ he says, ‘a case study for urban planners.’ In other words: ‘We want to do it right and in a way that benefits the people.’

In the years ahead, the area around Lüderitz will see the construction of one of the largest wind, solar and hydrogen plants in the world, including a desalination facility and deep-sea port. Balhao, the local councillors and the town’s administrators are committed and ready to seize whatever opportunities this opens up.

But what does being ready mean? The size of the workforce announced for the mega project is equal to the current population of Lüderitz alone – around 20,000 people. And that’s without counting accompanying family members or those who may turn up on the shores of the Atlantic in the hope of finding a job.

Elwin !Gaoseb

Elwin !Gaoseb

BMZ

BMZ

Green energy supply and fair cooperation

Although the town does not even feature on some maps of the country, for two years now Lüderitz has been a beacon of hope for Namibia – and for the European economy. The reason is green hydrogen. At the 2021 Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Namibia’s President Hage Geingob announced plans to develop an area twice the size of Luxembourg for the production of green hydrogen. The aim was ‘to change the lives of many in our country, in the region and indeed the world,’ Geingob said later. Lüderitz is set to become nothing less than a model for equitable cooperation between Global North and Global South.

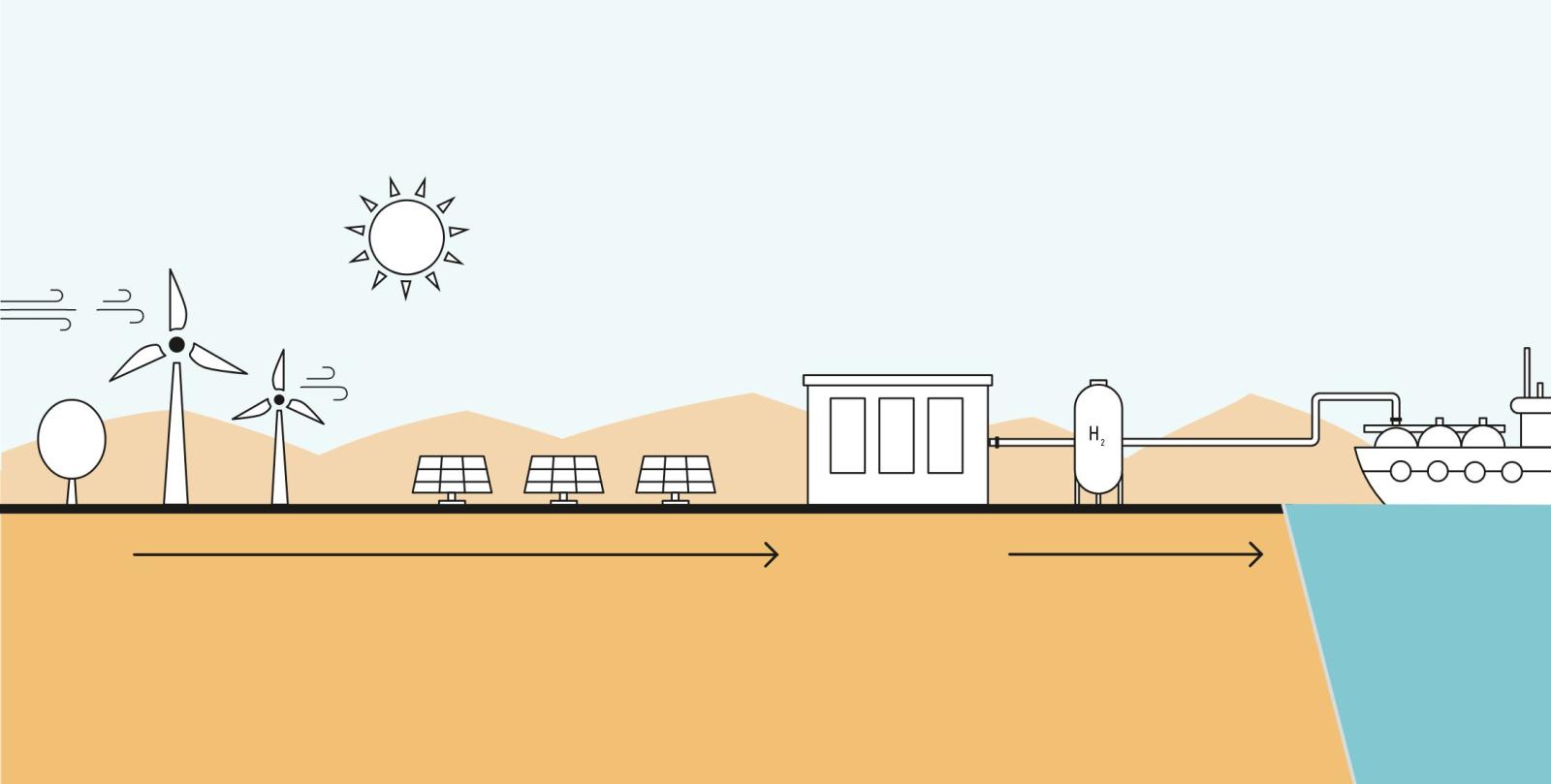

The region offers some of the best conditions in the world for generating electricity from wind power and solar energy – and therefore for climate-friendly hydrogen production. As a first step, the new plant is expected to be producing 300,000 tonnes of green hydrogen per year within five years at the latest – around one tenth of Germany’s forecast annual demand for 2030.

3st

3st

From the desert to the harbour of Lüderitz: planned green hydrogen production in southern Namibia

Focus on socio-economic development

Wind turbines and photovoltaics will provide as much energy as five to seven nuclear power stations. Namibia’s electricity consumption is currently just one eleventh of this, by way of comparison. And all this is just the start. Further development stages include plans for a tenfold expansion in hydrogen production at Lüderitz. This means there will be plenty of hydrogen available for export – once converted into derivatives such as ammonia.

But Namibia is aiming not just to become an energy supplier to the global green economy; its focus is also on the country’s socio-economic development. In addition to creating many new jobs, operation of the hydrogen plant is also expected to generate significantly higher tax revenues.

James Mnyupe, the Government’s Hydrogen Commissioner and advisor to the President, sees even more to it than that. ‘Long-term wealth is not purely dependent on a country’s natural resources, but rather on the nation’s ability to add value to those resources in a manner that improves the lives of its citizens,’ he says. The key principles here are economic diversification and green industry.

Partnership on equal terms

Simon Inauen, an expert in renewable energy, knows Mnyupe well. They have been working together for the past year. ‘Green hydrogen is not purely an energy issue,’ he says, ‘it’s interdisciplinary.’ Inauen came to Namibia three years ago on behalf of GIZ. His role then was actually to do with decentralised power generation using renewable energy in rural areas. But as the Namibian Government’s advisory requirements changed, so did his remit.

Inauen is now involved in five projects in the field of renewable energy and green hydrogen on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) as well as the EU. ‘Hydrogen offers the opportunity for a partnership of equals,’ says Inauen. Namibia is helping Germany and the EU to achieve their climate targets, while Germany is supporting Namibia in ensuring sustainable and socially just development.

Max Bosse

Max Bosse

Max Bosse

Max Bosse

The unique aspect of green hydrogen is the approach that brings together the various strands of development cooperation. On the one hand, hydrogen is a new environment for which states must first define the general conditions. Advisory work therefore covers a wide range of areas such as production standards and safety regulations for transport, as well as legal foundations for the development of value chains and expansion of renewable energy.

At the same time, the thematic areas are well known. GIZ provides support with training courses for ministries, as well as studies on job requirements, land use, supply chains and opportunities for value creation. The ramp-up of renewable energy, power supply in rural areas, urban development, vocational education and training and, not least, environmental protection also have an important role to play.

Lüderitz is now to show the world how all this can be interlinked. Environmental protection at the local level, climate action for the planet, exports, strengthening the domestic economy. Back to the port, in other words. It is one of the few points of access to the Atlantic, in a desert where the dunes come right down to the water’s edge. Only one road leads out; the nearest town is 350 kilometres away inland.

When urban planners think of Lüderitz, the colourful flaking plaster adorning its 19th-century colonial buildings, it is no wonder they see a town gradually waking from a long slumber, a Sleeping Beauty. Yet many of the inhabitants live outside the brightly coloured town centre in densely packed corrugated-iron huts, erected wherever the hilltops offer some protection from the wind. For with speeds of 11 or 12 metres per second, that is what makes the area so attractive for the turbines – the breeze off the North Sea has only half the power. But for the people here in south-western Namibia, the wind is a burden.

Max Bosse

Max Bosse

3st

3st

Promise of a better life

Mayor Balhao has a clear objective: ‘We are here to have a positive impact on people’s lives,’ he says. The municipality has built public toilets in the informal corrugated-iron settlements and the nearest school is within walking distance. It is also preparing construction areas that offer space for some larger plots and playgrounds, as well as water and secure electricity connections.

Industry and jobs are promises that give everyone here hope. So far, however, the administration and infrastructure have been designed for a small town, with a budget worth EUR 9 million. It is not just the hydrogen project that is gigantic: so are the challenges facing Lüderitz.

The Namibian Government has awarded the hydrogen production and accompanying measures to a private consortium. 15,000 workers are needed for the construction phase alone. Will they be accommodated at the construction sites and come to Lüderitz only at the weekend to go out or go shopping? Or will they compete for living space and push prices up? Such questions simply exemplify the enormous uncertainties ahead – and time is of the essence. Building work on the hydrogen plant is scheduled to start in 2025.

On behalf of the German Government, GIZ will support the Lüderitz administration in managing the expected rapid growth and shaping development – to ensure history does not repeat itself. The ghost town of Kolmanskop in the desert outside Lüderitz is a reminder of the former German colony’s short-lived diamond rush. But presidential advisor Mnyupe is certain: ‘This is not Kolmanskop. The big difference here is that we are mining an infinite resource.’ And involving local people and keeping a focus on the environment.

Max Bosse

Max Bosse

Environmental protection in focus

Namibia was the first African country to enshrine environmental protection in its constitution; today 44 per cent of the country’s land area, including the entire coastline, is protected. The planned wind and solar parks, hydrogen production, port and desalination plant around Lüderitz are also located in a national park. The adjacent marine area is so far Namibia’s one and only marine protected area (MPA). On behalf of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (BMUV), GIZ advises the Benguela Current Convention and its signatory states Angola, Namibia and South Africa on planning within the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem. The aim is to achieve a balance between sustainable use and protecting areas that are important for biodiversity. In future, this will also include the region around Lüderitz.

Max Bosse

Max Bosse