Work

The stuff that futures are made of

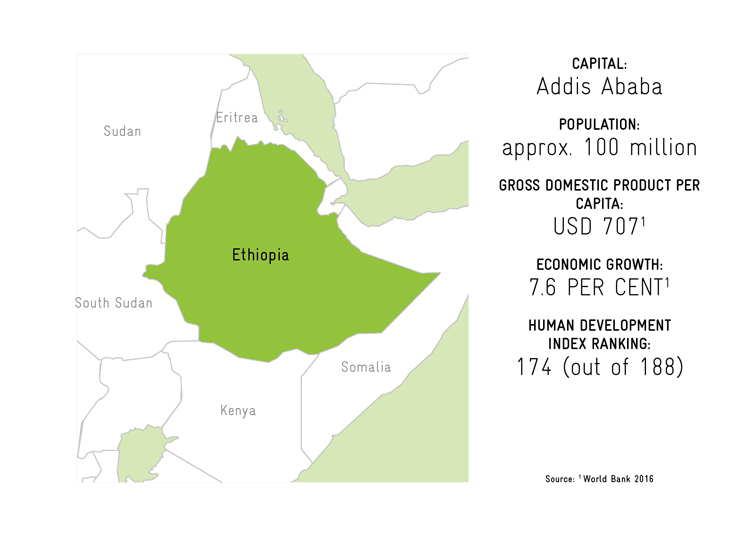

The Ethiopian Government has set itself an ambitious goal: it intends to create 350,000 jobs in the textile industry by 2022. It has commissioned the construction of industrial estates for the new businesses, with their own wastewater treatment plants and a reliable electricity supply along with massive halls, available for lease to investors. In Hawassa, a town with a population of 300,000 around 270 km south of the capital, Addis Ababa, the Government’s plan is already showing results. A total of 18 international textile companies have set up operations there, creating 20,000 jobs. In all, 12 industrial estates are planned across the country, with two already up and running.

But why is the Government placing such emphasis on the textile industry? Around the world, the industry has repeatedly hit the headlines with disasters such as the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh in April 2013. More than 1,100 people died there and over 2,400 were injured. The accident – for which the company running the factory was responsible – shone a spotlight on working conditions in parts of the textile industry, including poor wages and low social, safety and environmental standards.

Training for 10,000 managers and employees

There has been substantial progress in Bangladesh since the Rana Plaza disaster. For example, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH is helping to improve social and environmental standards in the textile industry. Working on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and with financial support from the European Union, it has so far trained 10,000 managers and employees in areas such as fair pay, fire prevention, and working safely with chemicals. Working conditions have improved in more than 800 companies as a result, and 200,000 mostly female textile workers are now aware of their rights.

The Ethiopian Government has been monitoring developments in Bangladesh closely and has worked with German experts from the outset to expand its own textile industry. Ethiopia already has legislation on working time: the working week can be up to 46 hours, with a maximum of 10 hours’ overtime. In building the new industrial estates, the Government is complying with rigorous environmental standards, because both it and manufacturers know that buyers from major fashion brands and consumers alike are placing increasing emphasis on sustainable production. Appropriate certification in areas such as wastewater treatment, emergency exits, accident prevention and fire prevention ensures the industry can compete on global markets.

The textile industry is a major driver of job creation.

so the country needs jobs. Mulugeta Mergia (25) and Jemal Shiferan (26) are just two of those already benefiting from the boom in the textile sector: they are recent graduates in textile engineering, and over the past 10 months, they have been working for a US company at the Hawassa site that manufactures men’s shirts. Mergia stands in a high, light-filled hall. A computer-controlled machine cuts the checked fabric into sections around a metre in length. Ten women then cut out shirt fronts and backs, sleeves, collars and pockets under guidance from the engineer.

Training is almost a guarantee of employment

To ensure that the skills of graduates like Mergia and Shiferan meet the requirements of businesses, GIZ is working in the areas of initial and continuing training in Ethiopia. Mergia has completed a six-week training course at the state-owned Ethiopian Textile Industry Development Institute in Addis Ababa, where around 400 graduates were trained on new machinery in the run-up to the opening of the Hawassa industrial estate. Every single course participant has found employment and since then, the Institute has trained 5,000 more textile engineers.

This additional skills development is important because universities in Ethiopia lack the technical equipment to offer practical, rather than just theoretical, training. It was not until they completed the six-week course that Mergia and Shiferan learned to use computer-controlled machines, to plan the manufacturing process and to carry out quality control. Shiferan says, ‘For me, the training course was a sort of bridge between what I learned at university and what really goes on at work. It’s made me a lot more confident.’

Ethiopia’s 350,000 vocational school students also lack access to practice-based training. Working on behalf of BMZ, GIZ is also engaged in this area. At the national TVET training institute, which trains teachers for all the country’s 900 vocational schools, curricula have been overhauled and improvements made in teaching quality. As well as textile engineering, the subject areas reviewed include the timber, metalworking and electrical trades.

Higher production levels boost wages

Very few of the owners of the clothing manufacturing companies in Ethiopia are locals. Most of them come from Bangladesh, China, India and Turkey. They bring experienced managers with them when they set up in Ethiopia, but many of the people they employ locally have never even seen the inside of a factory: they are typically from agricultural worker families, and many find training in a factory environment difficult.

The companies’ response is to plan training centres in Hawassa and in Mekelle, in the north of the country. GIZ is supporting them in doing so. The local investors’ association is GIZ’s partner in Hawassa, while H&M and a Bangladeshi textile company, DBL, are the partners in Mekelle. As Pierre Börjesson, H&M’s Africa representative, explains, ‘We want to improve efficiency. Training is a very essential part of that.’ The plan is for both centres to provide continuing training for up to 20,000 overseers, mechanics and quality controllers over the next few years. ‘Raising productivity gives the supplier better possibilities to improve the worker’s wages,’ adds Börjesson. Many Ethiopian workers are not paid a living wage: there is no statutory minimum wage, and almost one third of the population lives in extreme poverty.

Etsegenet Mitiku is one of those whom the initiative has helped out of poverty. The 24-year-old has been working in a textile factory on the outskirts of Addis Ababa for seven years. The factory is run by a Turkish company and produces T-shirts, blouses and baby clothes for the German market. The company employs 7,000 people. When she started as an unskilled worker, Mitiku earned just 400 Ethiopian birr a month (around EUR 12) but she now leads a team of 16 seamstresses and earns the equivalent of EUR 117 a month. The average monthly wage in Ethiopia is EUR 28. Mitiku and her husband, who is also employed, are able to rent an apartment, buy food and pay a family member to look after the apartment and their child.

Mitiku checks that seams are straight and buttons firmly attached. She then fills in a card for each of the women in her team, listing how many items each has completed that day. The target is 30 sets of children’s pyjamas. The factory manager says that Ethiopian workers are not as productive as those in Asia and that the wages reflect that. Nevertheless, the starting wage rises as soon as an employee is able to use all the different types of sewing machine in the factory. Aberash Mitike is 22 and has been working as a seamstress for six years. She now earns the equivalent of around EUR 70 a month. An ordinary seamstress cannot earn enough to rent a room of her own, so two or three single women typically share a room. Their standard of living is very basic: they cannot afford meat and eat rice and vegetables.

The seamstresses work from 08:00 to 12:00 without a break. They have an hour for lunch, which they eat in the factory canteen: the company provides a midday meal free of charge. The employees then resume work until 17:00. They are also entitled to paid holiday – 14 days a year to start with, with one further day for each year of service. Mitiku completed ten years of school education and would like to continue studying: ‘I’d love to be a bookkeeper,’ she says. She is aiming to work her way upwards in the factory, adding ‘There are a few Ethiopian managers here, and they are my role models.’

Annual textile fair in Addis Ababa

Purchasers from international companies attend the annual textile fair in Addis Ababa. The fair ran for the third time in 2017, but this was the first time it was organised in cooperation with Messe Frankfurt, the world’s largest trade fair organiser. GIZ has played a vital part in making the textile fair a regular fixture and establishing the link with Frankfurt.

H&M’s Pierre Börjesson thinks that Ethiopia offers enormous potential for the textile industry: ‘Right now, fabric is imported, e.g. cotton from India. But it’s possible to cultivate sustainable cotton here, the conditions for that are fantastic. Energy costs are low, too, and goods do not have to travel far to Europe.

It looks very much as though the Ethiopian Government’s plans are working – and the textile industry is indeed driving the country forward as it transforms from an agricultural society to an industrialised one.

Contacts

Training project: Nicola Demme > nicola.demme@giz.de

Sustainable textile manufacturing: Ulrich Plein > ulrich.plein@giz.de

published in akzente 1/18

JOBS IN THE TEXTILE INDUSTRY

Project: A skilled workforce for Ethiopia’s economy: capacity building in the education sector

Commissioned by: German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

Lead executing agency: Ethiopian Ministry of Education

Term: 2015 to 2018