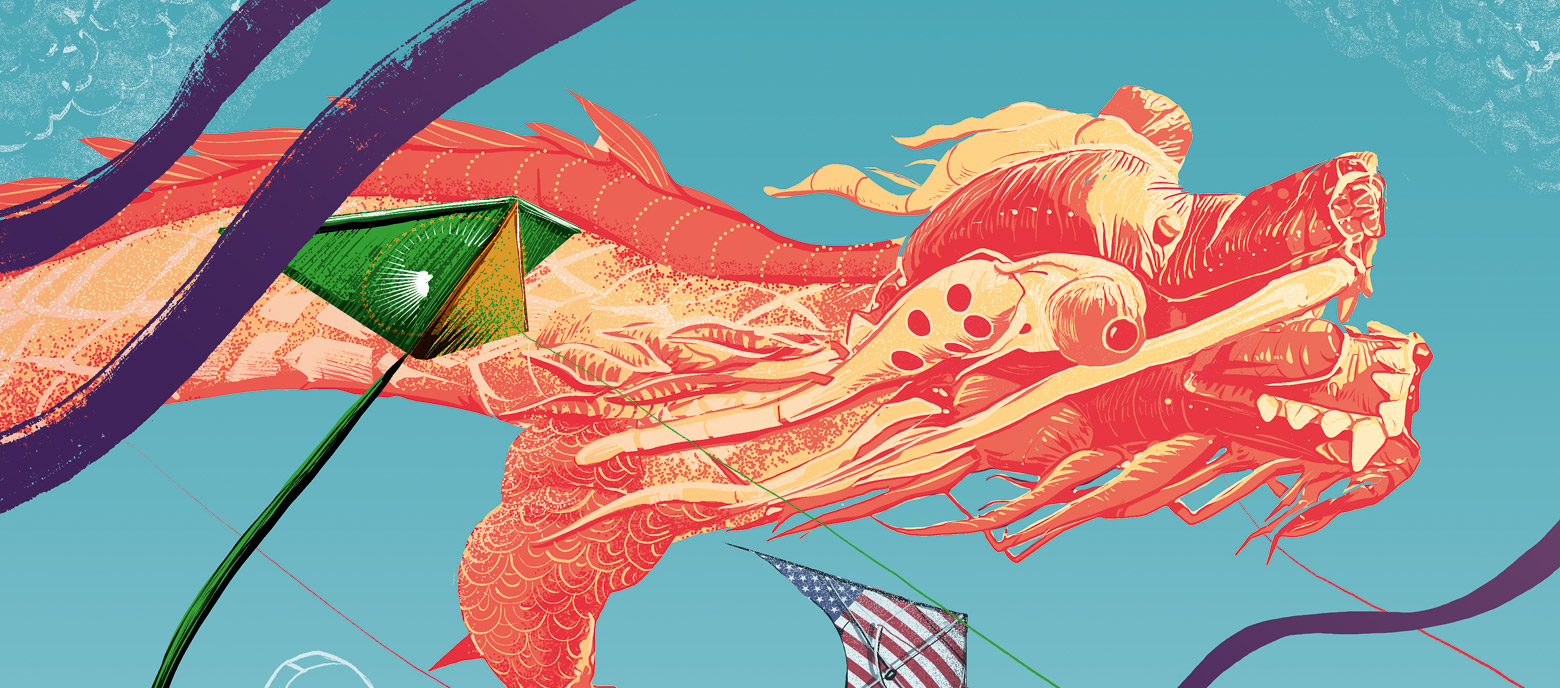

Essay China

China’s meteoric rise

Opinions about China diverge. There is scarcely another country in the world that provokes such controversial debate in the West. Enthusiasm and scepticism have for decades broadly balanced each other out in an intensive and controversial debate. This was already true in the thirty years following the victory of the Communist Party in 1949. But debates have only become more intensive and sometimes more contentious as a result of the rise of China, which began at the end of the 1970s under Deng Xiaoping.

China’s impressive economic development has turned the Western world upside down. When, at the Davos World Economic Forum, the leader of a Communist system announces to an astounded audience of top managers that he intends to champion free world trade, while the American President, the representative of the so-called free world, does exactly the opposite, it is apparent that parameters have shifted.

But China’s rise has not taken place in a vacuum. It also marks a geopolitical revolution, which appears to be replacing the Western-dominated world order. This revolution means that we are faced with the extremely difficult task of correctly interpreting China’s rise, to ensure that we do not make mistakes in the way we deal with this country and its growing global influence. But over the last 40 years, the West’s view of China has repeatedly been moulded by major misperceptions.

On the one hand, China fascinates us. On the other hand, the debates in the West often demonstrate a marked ignorance of Chinese politics, business, culture and history. We know very little about China in spite of the fact that we can hear and read things about the country almost every day. We spend more time dealing with our own expectations and fears than with the actual driving forces of Chinese politics. Let me take four examples to illustrate this observation:

‘We spend more time dealing with our own expectations and fears than with the actual driving forces of Chinese politics.’

In the late 1970s, when China’s reform policies were first launched, the West doubted whether ‘reforms’ were in fact conceivable in a Communist system. At that time, the China experts were largely in agreement that Communist systems could do many things, but that generating prosperity was not one of them. There was evidence enough from the Soviet Union, from Central and Eastern Europe and not least from the German Democratic Republic. But they were to be proved wrong. Over the last 40 years, China has genuinely generated prosperity – while retaining a Communist system. We would not have believed that a Communist system could lift hundreds of millions of people out of absolute poverty, while producing millionaires and even billionaires. But China has managed to. We were wrong.

Steady growth of the Chinese economy

As China opened up, we then dreamt of a vast market for our businesses and products. This dream came true. China can now show impressive figures. In 2017, exports hit almost USD 2.3 trillion, while imports totalled more than USD 1.8 trillion. GDP was USD 12.2 trillion. In spite of the steady growth of the Chinese economy, we couldn’t imagine back then that Chinese businesses would one day become competitors, firstly for German companies in China itself, then on third markets, and finally on our own market. It seemed normal to us to invest billions of dollars in China but we did not seriously expect that, one day, Chinese investors would come to Germany and invest in hidden champions, primarily in Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria.

Our third misconception is related to China’s political development. If this country had a large middle class, it was expected, it would only be a matter of time before this middle class demanded a political voice, Chinese society became more pluralist and finally democracy won through. There are so far no signs of this. The Communist Party remains unchallenged. The few dissidents play a larger role in Western media than in China itself.

Western self-deception

And finally, we are victims of a fourth misconception, which is an expression of our own hubris: we actually believed that we could tie China into the rules and institutions of the liberal world order dominated by us in the West. The famous statement of the American politician Robert Zoellick that China should become a ‘responsible stakeholder’ perfectly documents this self-delusion of the West. China is a ‘responsible stakeholder’ – but its definition is Chinese and not Western. Why should China do what is in our interest rather than what is in its own interest?

The simple conclusion is that China will not let itself be integrated or stemmed. The country is too large and already far too economically influential to allow anybody to dictate how it should conduct itself at global level. We have no choice but to engage as constructively as possible with a China that is becoming increasingly self-assertive and active in international politics.

No compromises

But what are the reasons for China’s strength and success, and what are its resultant global ambitions? To put it in very general terms, China’s secret is the consistent application of a principle Deng Xiaoping, the father of China’s reform policy, explained using the following metaphor: it does not matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.

The top priority is to retain the sovereignty of the Chinese state. China will accept no compromises on Xinjiang, Tibet, Taiwan or the South China Sea. Neither is it willing to cooperate in this respect. The second strategic priority is political stability. Anyone aiming to negotiate with China about the role of dissidents, human rights policy, opening up the Chinese market or the rate of reform, will find themselves facing partners who will only move once they can be sure that their own political system will not suffer as a result.

‘China is in the process of redefining its role in the world and challenging the Western economic model and way of life.’

The third priority is to hold course for economic growth. This is essential for the legitimacy of the Communist Party. This is another area in which China will not countenance compromise, in spite of all the problems that the unprecedented growth of the last 40 years has brought. The fourth, resulting priority is to consistently build China’s global influence. China is in the process of redefining its role in the world and challenging the Western economic model and way of life.

Under President Xi Jinping, China’s Communist Party is pursuing a strategy of pushing back the West, in particular the USA. Based on strategic patience, pragmatism, economic performance and disruptive technology, the country aims to become the most powerful and influential country in the world by the mid-21st century at the latest. No Chinese politician will admit it openly (yet), but the signals are clear for all to see. In the West, we apparently don’t want to see. We brand all pointers in this direction propaganda, and fail to grasp China’s growing self-assertiveness, with all the consequences thereof.

Global ambitions

Three examples illustrate this clearly: China’s increasingly dominant role in Africa has been irritating Western observers for years, and is a major challenge for Western development cooperation. Without imposing political conditions, China is investing in infrastructure measures that have one main purpose – to meet China’s own demand for raw materials. This policy nevertheless has spin-offs that are beneficial for African economies and Chinese investment is thus welcome. Occasionally voiced criticism that China is acting like an old-time colonial ruler and that too few local workers are employed are of no more than secondary importance. Examples like Zambia, for instance, which has seen uprisings against working conditions in Chinese companies and criticism of Chinese takeovers of local companies, in no way call into question the overall picture.

The position is similar with China’s New Silk Road project. Since President Xi Jinping first announced the One Belt, One Road Initiative, or as it is now more elegantly termed the Belt and Road Initiative, in 2013, it has become a major geopolitical project. With a gigantic infrastructure network, tapping into new markets and creating new value chains, China is endeavouring to extend its political influence, and increasingly also its military influence beyond Central Asia right up to Europe, and to become an antipole to the USA’s claim to be the leading world power. There is no foreign-policy initiative that more clearly illustrates China’s claim to global power.

Risk of a trade war

US President Donald Trump’s efforts to stem China’s growing influence with the help of a trade war will do nothing to change this. This non-military war is about far more than America’s balance of trade deficit. It is about the entire spectrum of the rivalry between two major powers, who are struggling for supremacy in the spheres of security, economics and technology in the 21st century. This conflict would not be resolved by ending the trade war. The question as to how the conflict can be shaped and facilitated is crucial for economic cooperation and peaceful coexistence, and for resolving the fundamental global issues facing us in the first half of the 21st century.

In conclusion, China’s rise is unstoppable, assuming it does not suffer any major internal crisis or war. The latter scenario is an option that is certainly being discussed in the USA, but less in Europe. A scenario of this sort cannot be entirely discounted: even in Ancient Greece the ‘Thucydides Trap’ was a known concept – a military conflict between a rising and a waning power. Currently there are no real signs of either an internal crisis or a military conflict. Unforeseen events could, however, reverse this situation at any time. We would then all be well advised to consider China’s rise as legitimate and as a fact. In future China will be at least as important for Germany and for Europe as the USA has been in the past.

published in akzente 1/19

Gathering momentum

Report China

‘China is hungry for success’

Interview Zheng Han

Faster, higher, further

Infographic China