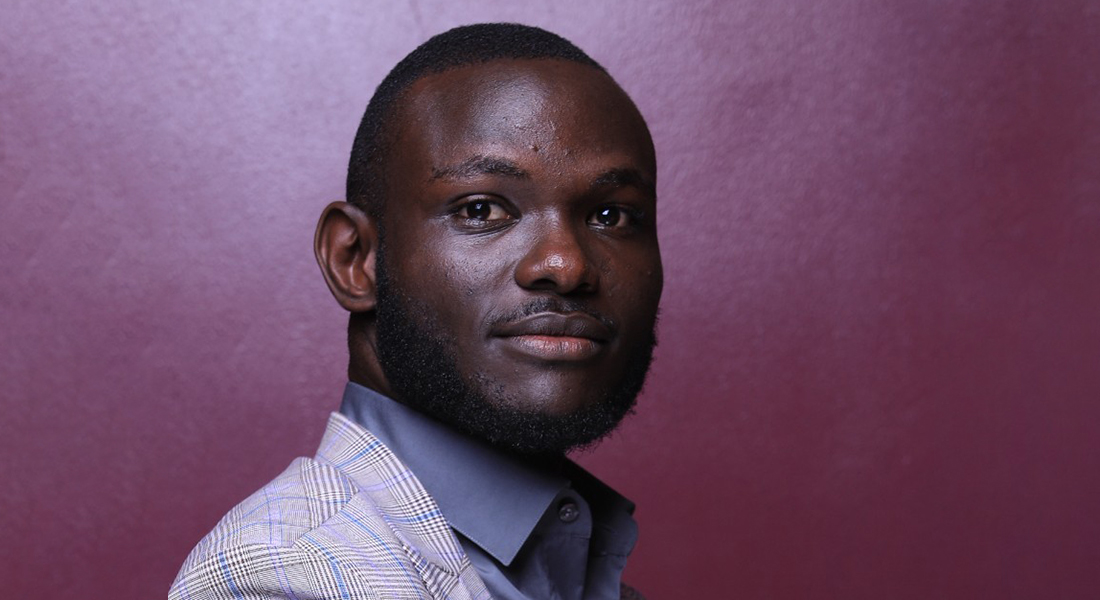

To keep up with the latest developments in his field, Edgar Ssensalo is constantly upgrading his knowledge and skills. Two years ago, he attended a bootcamp on Machine Learning for Earth Observation (ML4EO). ‘I saw the course and was immediately intrigued. Fortunately, I was able to pass the prequalification assessment and got accepted in,’ he says.

Artificial intelligence for agriculture

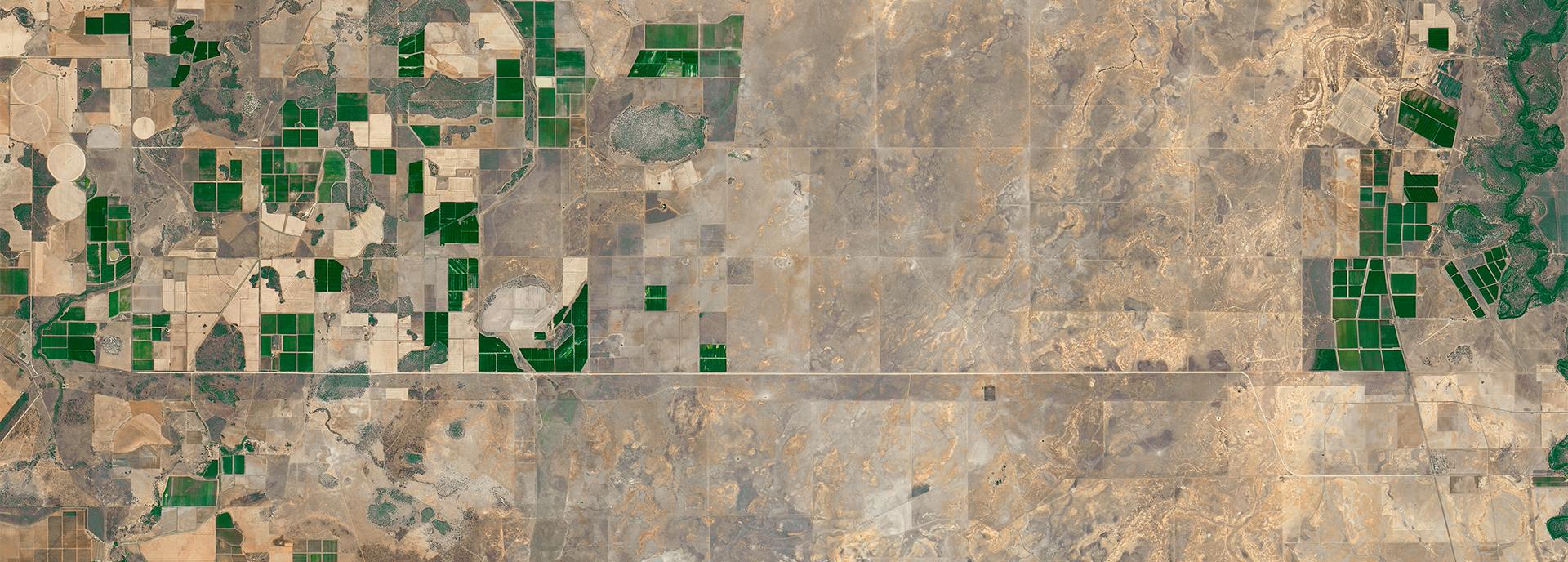

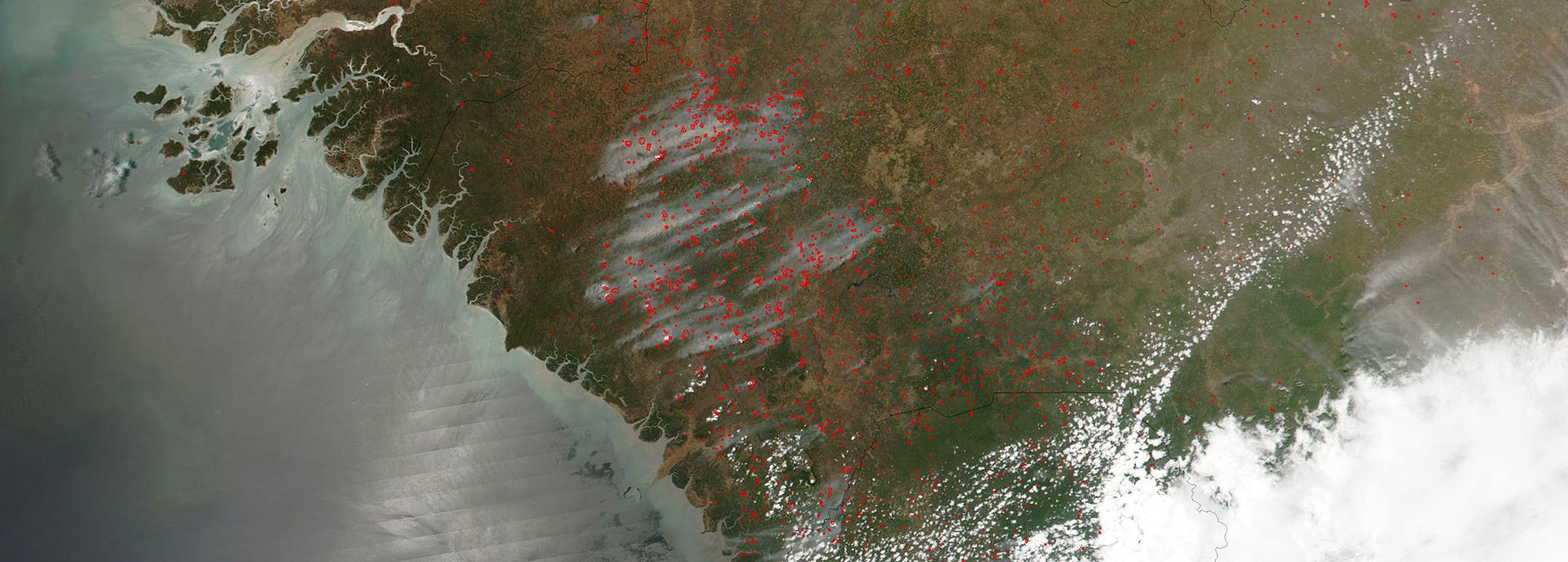

Machine Learning for Earth Observation involves analysing and processing satellite data that not only tells us a lot about the current condition of the regions observed, but also allows forecasts about the future to be made through the use of modelling. This is particularly important for agriculture, which plays a significant role in Africa as it is the key economic factor. However, it requires specialists who are able to read and process the data. Just as ultrasound images are not straightforward to understand, special knowledge is also required to interpret satellite data.

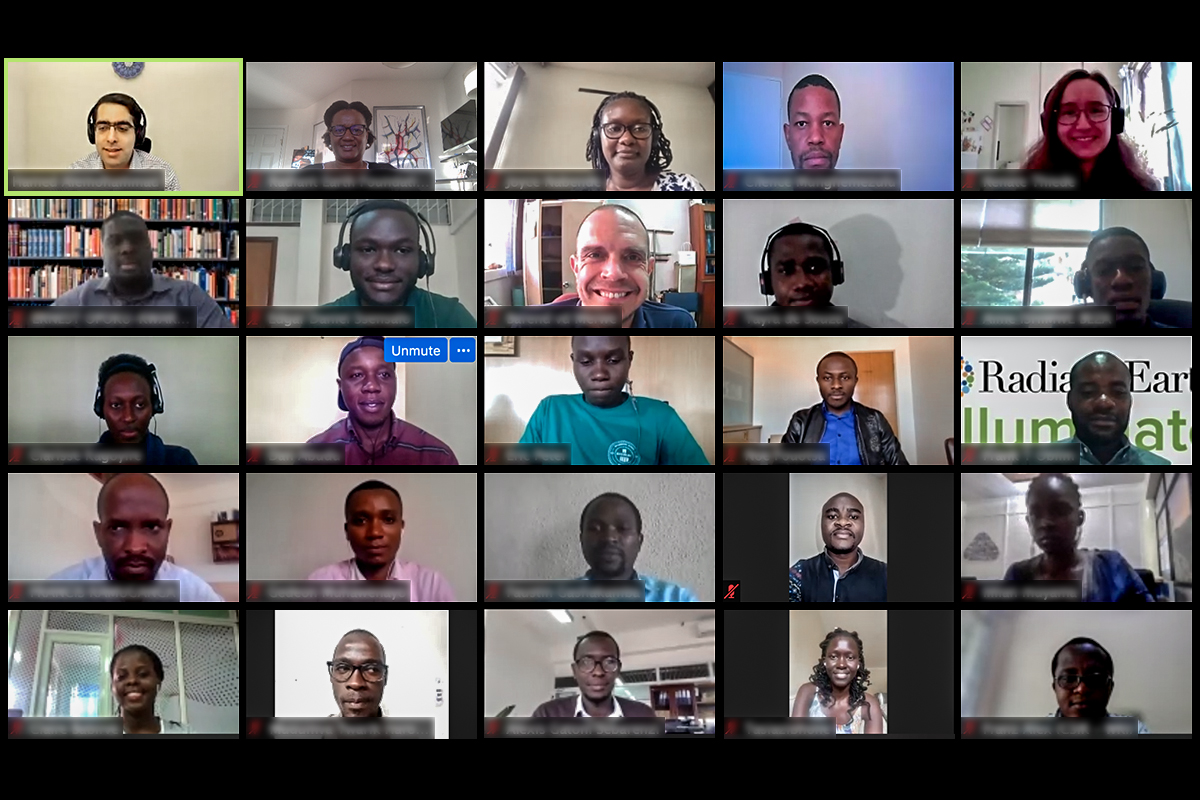

This knowledge is taught at the bootcamp, a two-week intensive course supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the German Government. Participants learn how to process satellite data so that it can be used to draw intelligent conclusions. For example, whether a country is growing enough to be able to continue feeding its population in years to come, or identifying crop types using satellite imagery data, what condition the soil is in and what is the most promising thing to grow in a particular region. The data can also be used to record deforestation rates. ‘It’s fascinating, but at the same time very complex,’ says Edgar Ssensalo.