Report

Tracking down the truth

It is a piece of human skin about the size of a sheet of A4 paper, dark and leathery; ‘mummified’ is the term used in forensics to describe it. Guadalupe de la Peña and Franziska Holz unwrap it carefully from the blue paper protecting it and lay it gently on a dissecting table. The piece of skin is a valuable find and may help to answer the question of whose body it came from.

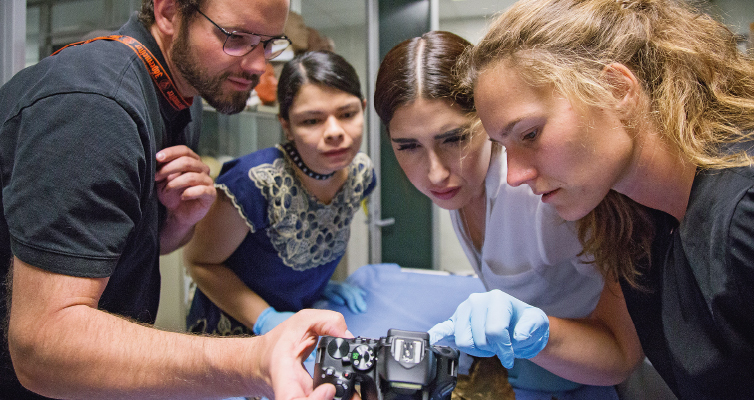

German forensics experts Franziska Holz and Christoph Birngruber, their Mexican colleague Guadalupe de la Peña, and anthropologist Dalia Miranda are trying to get closer to answering that question. All that remains of this individual, whose body was found a year ago, is this piece of skin, the skull and some bones. And all anyone can say for sure is that he was a male aged between 31 and 51.

Every aspect of the work is hard. And it begins with looking carefully. Under the artificial light of the basement of the Forensic Science Institute in Guadalajara, the four professionals peer at the piece of skin. If you look carefully, you can see some coloured marks that were once part of a tattoo. More than five million people live here in Mexico’s second largest city, in the west of the country between the Pacific and the capital, Mexico City. This is where the Mexican cartels began life, almost half a century ago, and this is where they still compete for routes and territories for drug trafficking and other illegal activities. And they are in a battle with the state. Guadalajara and the state of Jalisco are the epicentres of violence in Mexico.

In 2019, 100 people were murdered every day in this Latin American country. The National Search Commission believes that a total of more than 61,000 people have disappeared nationwide, including 9,000 in Jalisco. 2,700 people were murdered in the state last year. Many of the victims are buried in mass graves, and last year alone, almost 900 such graves were discovered across Mexico, many of them in and around Guadalajara.

Most victims of cartel violence have no means of identification on them, and most are naked when their bodies are found. ‘This is the sad reality we are facing here,’ says Guadalupe de la Peña. Every day, the Institute typically receives eight to ten bodies, of which around half are unidentified. The task the experts face is difficult. How can they find out who these people were? Identification is often made even more difficult by the condition of many of the body parts.

Tattoos provide a clue to identification

Forensics experts in Germany would be able to rely on DNA samples, dental records or simply fingerprints. But Mexico does not have a central fingerprint database, and Mexican dentists do not keep detailed dental records. ‘That means we have to rely on secondary characteristics, such as tattoos,’ explains Franziska Holz.

She and Christoph Birngruber worked with Mexican colleagues for six months from October 2019 to improve identification. On behalf of the German Federal Foreign Office, GIZ is supporting the Latin American country in strengthening its forensic science institutes. ‘Identification needs to be better and faster,’ says Birngruber, who normally works at the university hospital in the German city of Frankfurt. There is a growing backlog of cases for identification, creating an increasing workload for the institutes – and delays.

Every day, mothers, wives and children arrive at these institutes looking for sons, husbands or brothers who have disappeared. They go directly to the forensics institutes rather than to the police because they mistrust the investigating authorities, says Mónica Chavira, a 56-year-old woman with some very firm views. She is a member of the ‘Por Amor a Ellxs’ (Out of Love for Them) collective, a self-help group for women whose husbands and sons have disappeared without trace. Since September 2013, Chavira has had no news of her husband or her son. They have simply vanished without any trace whatsoever. For her, and for other families, the uncertainty is extremely distressing.

‘The police and the public prosecutor are not doing their job properly,’ she says, referring to serious shortcomings in the security and justice system. Investigations are inadequate, if they take place at all, says Chavira, either because the relevant agencies do not know how to proceed or because they are hand in glove with the cartels.

Strengthening the rule of law

Strengthening the rule of law is one of the major challenges facing Mexico. This includes giving the victims of violent crime a name. On behalf of the German Federal Foreign Office, GIZ is working with Mexican state institutions and civil society to improve the identification of the deceased as well as the structures underpinning forensics and the national system for searching for missing persons. The programme provides a range of support for devising and implementing an ‘extraordinary mechanism’ for identifying more than 37,000 unnamed bodies currently stored within forensics institutes, and for exhuming thousands of graves, many of them mass graves. To record victims’ details effectively and to ensure that the recording system operates beyond state boundaries, it is compiling databases and providing appropriate training for Mexican partners. The programme works closely with the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross and the German Embassy in Mexico. It has published newspaper and journal articles in Mexico about the cooperation with German forensics experts. Furthermore, public discussion is now focusing increasingly on structural changes in the process of identifying unnamed bodies.

Contact: Maximilian Murck maximilian.murck@giz.de

Over recent years, Chavira, a teacher, has on more than 30 occasions appealed to the police, the public prosecutor’s office and the Forensic Science Institute in Guadalajara to search for her husband and son. Every time, she has been asked to submit the same documents and answer the same questions – about age, height, fingerprints, identity documents, permanent features, and DNA samples – but so far to no avail. ‘It’s great that people from other countries are now taking a look at our systems,’ she says. ‘The pressure from foreign governments will help improve things.’

In order to achieve this, the Mexican and German forensics experts have worked together to systematise databases and have, for example, categorised distinguishing features such as scars and tattoos. This means that specific features found on a body can be compared with characteristics reported by relatives. ‘We wanted to ensure that families don’t have to go through all the information again every time they make a request but that forensics institutes can use data already on file,’ says Franziska Holz, a forensics expert with Frankfurt’s Goethe University. It’s an ambition she shares with Guadalupe de la Peña, who is thrilled at how the Mexican-German team is collaborating: ‘The great thing about working with Franziska and Christoph has been cooperating on making real improvements.’

Infrared photography and hydrogen peroxide

New methods make it easier to discover more identifying marks. Hydrogen peroxide, for example, is fairly easy to use. Applying a dilute solution of this pale blue liquid, a compound of hydrogen and oxygen, lightens the skin for a while, so tattoos stand out more. And where bodies are already mummified, infrared photography can help. The Mexican-German team is using this technology to decipher the tattoo on this A4-size piece of skin.

MEXICO

Capital: Mexico City / Population: 126.2 million / GDP per capita: USD 9,180 / Economic growth: 2.1 per cent / Human Development Index ranking: 76 (out of 189)

Source: World Bank 2018

Mexico is the world’s largest Spanish-speaking democracy, but the rule of law faces a crisis there. The high murder rate, tens of thousands of missing people and almost complete impunity even in the event of the most serious crimes are devastating the country. The current government took office in late 2018, pledging to tackle this humanitarian crisis.

Franziska Holz takes a paintbrush and carefully brushes the earth away from the fragment, which comes from the victim’s back and is adorned with a large tattoo. An outline and traces of colour can be seen. The team turn the piece of skin around, throwing out ideas in a mixture of German, Spanish and English as to what the design might be.

A single-lens reflex camera makes the task easier: simply changing the filter turns it into a valuable identification tool. Photographing solely infrared light means that blood can be detected on dark fabric, for example, or pigments in tattoos show up. De la Peña photographs part of the skin. The display on the digital camera reveals a black and white image of what looks like a clown or a mythical creature. The young forensics expert then combs the internet for comparable images. ‘This could be it,’ she exclaims suddenly. ‘It’s a harlequin.’ Piece by piece, and centimetre by centimetre, the team photograph the section of skin. Later, anthropologist Dalia Miranda scrutinises the computer images, trying to piece the puzzle together. Her work is just as challenging as that of her forensics colleagues. The finds Miranda and her colleagues examine range from single bones to complete skeletons. They have to assess whether remains belong to one individual or several. Traces of recent injury to bones can also reveal the cause of death. In most cases, only bones or skeletons remain of a victim, making the work of anthropologists crucial to the process of identification.

‘Our hope is to contribute to social peace in Mexico and improve trust in the rule of law.’

A few weeks later, the tattoo has not been completely deciphered, but it is clear that it is based on three interlinked heads of mythical creatures. Dalia Miranda finds similar tattoos on the internet. This will enable forensic science institutes to search the databases for reference to this kind of tattoo in the information families have registered about missing loved ones.

Such painstaking identification processes are needed for many of the victims. But, as Guadalupe de la Peña knows, the work of bringing cases to a successful closure is important: ‘It means families can finally start grieving.’ And that is one of the main reasons she does this work. ‘In Mexico, there is less focus on the victims,’ she argues. The system is not set up to show sensitivity and empathy when dealing with families, she adds, but ‘I am so glad that the work we do can help them achieve a little more peace of mind.’

published in akzente 2/20