Essay Waste

Throwaway lifestyles

‘Dispose of disposables!’ That is the basic tenor of the headlines emerging from the European Parliament this spring. Good news! Europe is leading the way in the fight against the plastic waste that is turning beaches and oceans into rubbish tips. Members of the European Parliament voted to ban ten frequently sold single-use plastic products as of 2021. They include cotton buds, drinking straws, disposable cutlery and plates and expanded polystyrene containers. These throwaway products are all among those most often found on the beaches of 17 EU member states.

But there is still a long way to go. While banning single-use plastic products is a step in the right direction, its impact is minimal given the overall situation. These throwaway products make up only a very small percentage of total plastic consumption. In Germany, Europe’s largest economy, they account for a total of about 105,000 tonnes, whereas three million tonnes of plastic packaging was used over the same period. After a short time, most of this packaging also ends up as waste. That means that the globally applauded EU regulation is reducing this torrent of plastic waste in Germany by only three per cent.

The ban on single-use plastics is only a partial solution to a partial problem. Even if the EU’s move is copied on other continents, it is nowhere near enough. Not to protect beaches, not to stem the growth of the gigantic collection of plastic in the world’s oceans, and not to end the microplastic contamination of our seas and oceans. This is invisible and much of it comes from other sources, including tiny fragments of vehicle tyres. The main problem is the waste of resources caused by the huge quantities of cheap plastics on the markets, which also contain an entire laboratory of chemical additives. The EU’s ‘waste strategy’ does little or nothing to solve these problems.

Dramatic development since the advent of the plastic age

One thing is certain – the volume of waste is growing worldwide, in industrialised countries as in developing countries – not only, but particularly, plastic waste. Since the advent of the plastic age in the 1950s, around eight billion tonnes of plastic have been manufactured worldwide. Currently, global annual production is just under 400 million tonnes, which is roughly equivalent to the weight of two thirds of the people living in the world today. Experts believe that the quantities produced could quadruple by 2050 if no action is taken to change this course.

‘Our planet is drowning in waste. This is every bit as dramatic as climate change. The flood of waste is as clear an illustration as possible that we are stretching the ecological limits of Earth to breaking point.’

Our planet is drowning in waste. This is every bit as dramatic as climate change. The flood of waste is as clear an illustration as possible that we are stretching the ecological limits of Earth to breaking point. Scientists are already talking about the Anthropocene, the epoch dating from the start of significant human impact on the planet – in the form of climate change, soil erosion and the destruction of virgin forests, to name just a few examples. The true impact of the Anthropocene only becomes clear, however, if we understand it as the age of waste. Geologists in thousands of years will still find it easy to date the start of this new era, thanks to the fragments of plastic that have found their way to every corner of the earth over the last 70 years, all the way to the frozen wastes of the Arctic and the peaks of the Himalayas.

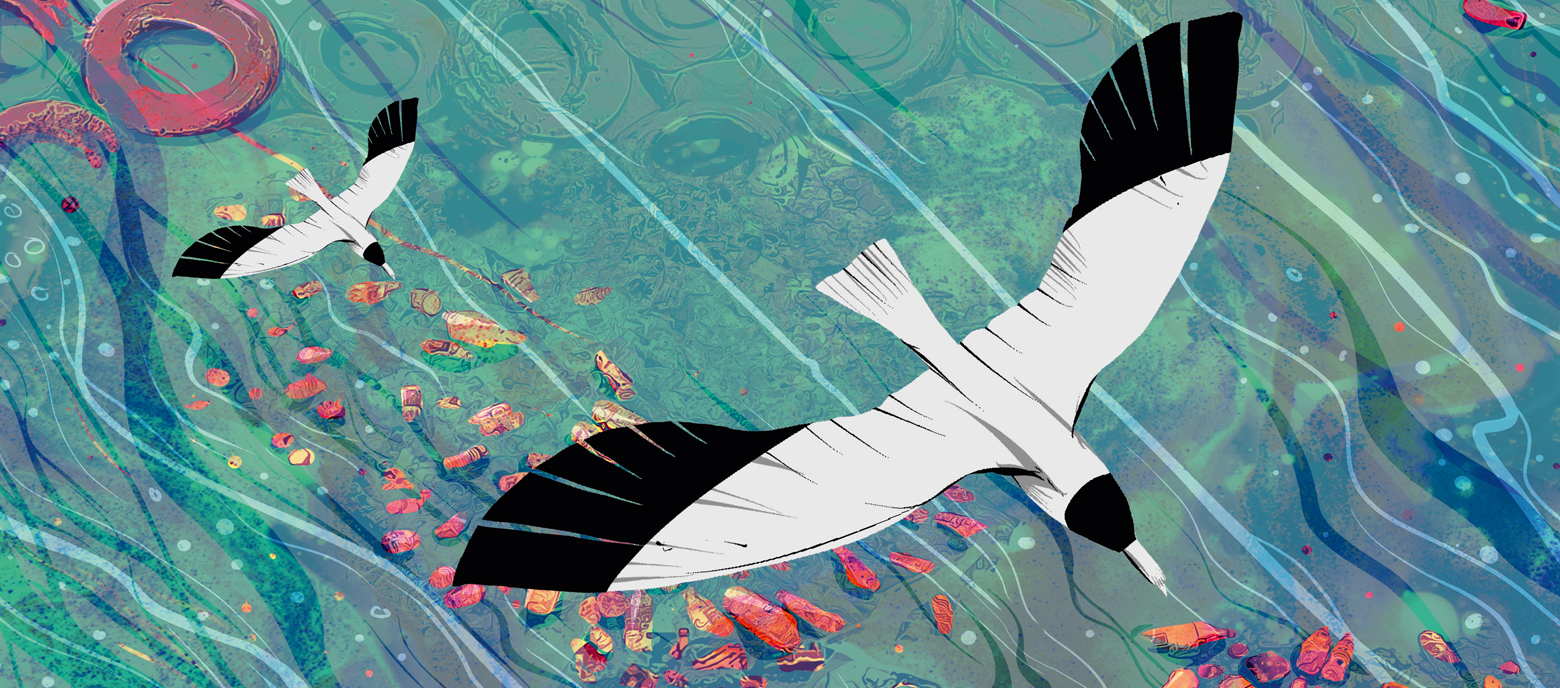

Quite apart from the photos of the the world’s five ocean gyres and the seabirds, turtles and whales that have died after dining on a menu of plastic, the consequences of the torrent of waste are dramatic – especially in developing countries. Unsecured landfills contaminate drinking water, burning waste does the same to the air people breathe, and solid waste blocks drainage channels, increasing the threat of flooding.

IN THIS ARTICLE

1. The STATUS QUO

Where we stand and why the EU regulations on single-use plastic items do not go nearly far enough.

2. THE PROSPECTS

How people are increasingly destroying the resource base on which they depend.

3. THE VISION

What approaches are there to address our gigantic waste problem sustainably.

An entirely new scale of waste

People have always produced rubbish. It only started to become a problem during the Neolithic revolution, when arable farmers began to settle, and settlements grew and grew. In what is today the Middle East, the first mountains of waste accumulated, with layer upon layer of rubbish, because sooner or later there was no more space. Turkey, Lebanon and Syria are full of the remains of ancient middens, Troy being the best known example. Even in New York, archaeologists have discovered that the streets of Manhattan are almost two metres higher today than they were 350 years ago – the Big Apple stands on foundations of trash and rubble.

Today, however, we are facing a new dimension of waste problems, because the number of people on the planet is rising exponentially, because people around the globe are copying the resource-intensive lifestyle of the first countries to industrialise, and because modern waste contains contaminants that have no place in the biosphere. Moreover, plastics account for ‘only’ 12 per cent of global waste. The rest is made up of an extremely wide variety of other materials – from cigarette butts in the gutter to metals and materials like rare earth elements, which are valuable but are still thrown away, to hazardous toxins and nuclear waste. Industrial waste is becoming an increasingly worrying problem, too, with slags, plaster and silver foil. The electric waste spawned by rampant digitalisation in particular is in a class of its own. This waste is difficult to recycle and contains toxic substances including mercury and lead.

Another problem that tends to be ignored is that some waste directly compounds the greenhouse effect – like coolants used in refrigerators, which are often incorrectly disposed of, and insulating foam, which is produced using gases that are bad for the climate. Even organic waste turbocharges climate change if it is buried along with other waste in landfills, creating the necessary anaerobic conditions for the production of the greenhouse gas methane.

An enormous waste of raw materials

Environmental scientists have described our modern production patterns as a massive machine to destroy raw materials, in which products or services are more or less a by-product. In industrialised countries, nearly 100 tonnes of non-renewable raw materials are used per capita every year, according to the recently deceased resources expert and former deputy director of the think tank the Wuppertal Institute (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie), Friedrich Schmidt-Bleek. That is between 30 and 50 per cent more than in the poorest countries of the world.

‘As with climate change, a radical turnaround is needed in the way we use raw materials. Waste must be drastically reduced in manufacturing, consumption and solid waste management.’

This becomes an ecological problem primarily because on average, more than 90 per cent of the resources moved in and taken from the natural environment end up as waste en route to production and after products have been used. Recycling quotas are low. Even in highly developed European economies, for instance, no more than 13 per cent of resources enter the circular economy. Globally, this figure is just seven per cent.

The answer must be to make better use of materials

The key to ending the high level of resource consumption and therefore also the torrents of waste is to achieve better resource productivity – i.e. to make more effective use of the materials to produce the services required. According to Schmidt-Bleek, global resource use must be halved at least. In industrialised countries, consumption will have to drop to just one tenth of the current level. Plans are in place in many areas – in the transport sector, for instance, these savings and more can be achieved by leaving cars at home and cycling instead. Up to now, there have been no consistent efforts to put these plans into action. This is partly because the prices of raw materials are too low and do not reflect the ‘ecological truth’, as former German Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker put it. In Germany, per capita consumption of natural resources has actually risen again over the last few years.

As with climate change, a radical turnaround is needed in the way we use raw materials. Waste must be drastically reduced in manufacturing, consumption and solid waste management. Eco-intelligent product design can facilitate high-level reuse and recycling within a circular economy. To date, the EU’s Ecodesign Directive focuses only on energy efficiency. In the future, we must also take into account material efficiency, service life, recyclability and reparability. Taxes on raw materials must be at a level that is felt, and rigorous recycling is needed along with a change in consumer practices.

Leasing rather than buying

New business models can also be an important tool, with products like household appliances no longer being sold but leased for a certain period. The advantage of this is that manufacturers retain ownership of their products and therefore design them to ensure optimum reusability and recyclability. The aim is to have a virtually closed circular economy. But consumers, too, must do their bit. The way we purchase can definitely influence the way resources are used. Consumers can buy long-life products rather than products that are destined to go more or less straight from the factory to the rubbish tip. They can use exchange platforms for home furnishings, clothing and tools. They can take their own bags, baskets or rucksacks when they go shopping and buy unpackaged goods as much as possible.

However, we will need to do more than this if we are to address the acute plastic crisis. Experts believe that the most spectacular problem, worsening marine litter, can be resolved. This would require proper collection and recycling systems for plastic waste to be set up in developing countries – according to the World Bank, 90 per cent of waste is simply thrown away or randomly burned in poor countries. The majority of the plastic waste that ends up in the world’s oceans comes from Asian and African states including China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Egypt and Nigeria, entering the oceans via just ten major rivers. These measures could put a stop to this. By contrast, it is deemed to be difficult, if not impossible, to remove waste from the oceans once it is there.

‘Consumers, too, must do their bit. The way we purchase can definitely influence the way resources are used. Consumers can buy long-life products rather than products that are destined to go more or less straight from the factory to the rubbish tip.’

Unfortunately, the main producers of waste still lack awareness of the problem, although encouraging decisions have been taken. India, for instance, has voted to ban single-use plastics from 2022. Kenya has ended the use of plastic bags, and Israel has halved the number of plastic bags in the sea. But of the main problem countries, only Indonesia and the Philippines have signed up for the Clean Seas campaign launched by the UN in 2017, demonstrating that a lot needs to happen before the awareness of the danger posed by plastic matches the awareness of climate change.

The goal is binding international rules and regulations

Nevertheless, the goal must be to adopt an international agreement, binding under international law, which commits governments to end plastic pollution. Not only in our seas and oceans. The key must be avoiding plastic, ensuring multiple use where it is unavoidable, and putting in place a closed circular economy for plastic. The Berlin-based expert Nils Simon has presented a proposal, based on the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. It includes a convention with a binding overarching goal in conjunction with national action plans. Forging ahead with this plan would be beneficial, not least for the EU, which has already become a forerunner in the field of international climate action.

published in akzente 2/19

Kick-off at the scrapyard

In focus: Waste

‘The time to act is now’

Interview

As far as the eye can see

Infographic Waste