Sustainable agriculture

Rich harvest in Ethiopia

In the highlands of Tigray, Ethiopia’s northernmost region, the roads through the mountains are steep and the landscapes breathtaking. But something is amiss. The vast fields of dry and deforested land in the valleys provide a stark contrast to the green, fertile mountain slopes. As we leave the asphalt behind and drive into the heart of the woreda (district) of Raya Azebo, the clouds of dust flung up by our vehicle linger in the air. Trees and farmlands are clearly in need of rainfall, the cattle are visibly malnourished and farmers worry about the meagre harvest they can expect from their parched fields.

About 1.5 kilometres off the main road we come across a lush oasis. The trees here abound with fruits, the fields are full of cereals and vegetables. One of those working on the land and proudly inspecting his healthy crops is Berhanu Hiluf, a 38-year-old priest from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. On his quarter of a hectare of farmland, he grows papayas, mangos, bananas, oranges, coffee and teff, an Ethiopian variety of grain.

Food security and consequences of climate change

This part of Raya Azebo was not always the cornucopia it is now. Until seven years ago it was as barren a landscape as the one we drove through on our way here. But things changed dramatically for Berhanu Hiluf and his village in 2008, when a programme geared to sustainable land management was introduced.

The programme focuses primarily on the rehabilitation of land for agricultural purposes. This is a difficult task, with direct consequences for livelihoods, since over 30,000 hectares of land are lost each year in Ethiopia as a result of land degradation. The programme additionally addresses food security challenges and implements measures to combat the consequences of climate change. It has been introduced in 177 districts across Ethiopia, and is managed and implemented by the Ethiopian Government and its army of 70,000 agricultural extension workers – Ethiopian staff dispatched to communities to disseminate information and train people in rural areas. The government receives support from GIZ, working on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development in collaboration with KfW Development Bank. The budget is cofinanced by the World Bank, the European Union, Norway and Canada.

Less fertile land for a growing population

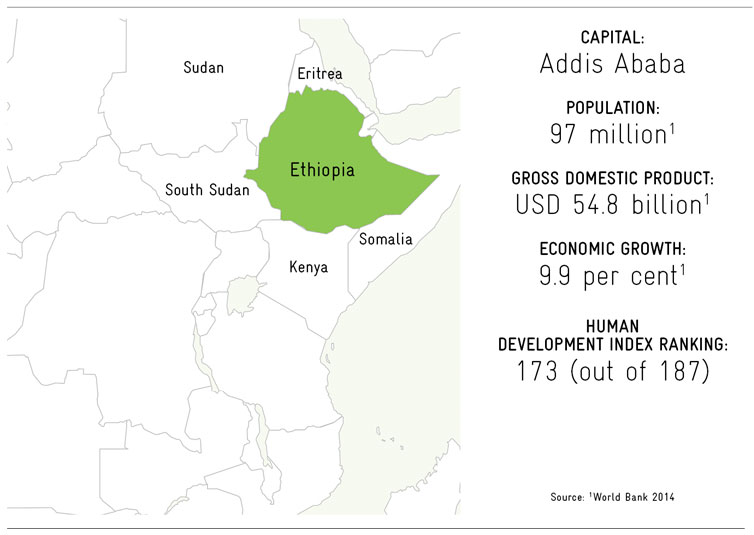

Like Berhanu Hiluf, most people in Raya Azebo live off the land. For generations, knowledge of rearing livestock and farming the land has been handed down from father to son, from mother to daughter. However, traditional approaches to farming are no longer adequate – even in years with good rainfall. And this is a consequence of a relatively new phenomenon in Ethiopia: overpopulation. Whereas the country counted approximately 40 million people in 1985, Ethiopia is now Africa’s second most populous nation, with over 97 million. And population numbers continue to rise. Less fertile land for a growing population means lower per capita agricultural production. For a country such as Ethiopia – where 80 per cent of the population are smallholder farmers, and agriculture accounts for 41 per cent of gross national product – this can have disastrous consequences.

Previously, if land had become overused and in need of rest, farmers would gather their belongings and move to new fields to continue farming. There was also ample land for cattle to graze. Population growth has constrained farmer mobility and finding pastureland has become a challenge. Increasing deforestation and soil degradation are the result.

Flooding and soil erosion

For 15 years, Hiluf tried different ways to get a respectable harvest from land that was overgrazed and suffered from soil erosion. He remembers well the day seven years ago when the new soil management programme was introduced at a village meeting. The farmers’ reactions ranged from scepticism to outright rejection. Changing farming methods that had been passed down for generations would be a challenge, to say the least. In particular, a proposed ban on free grazing for cattle faced stiff opposition. Farmers were concerned about the additional cost and work involved in having to grow feed for the herds.

Once the confidence of the farmers had been won, however, improvements came thick and fast. These included the construction of retaining dams. Hiluf helped build dams along a gorge, which gave rise to new arable land. One of those plots is now his. This has been a life-changer for him, he says. He explains how previously they had used only small, makeshift dams made of wood. During the rainy season, the floods would usually destroy them. ‘The project supplied the materials and knowledge to close off the upper catchment area. The flooding stopped immediately.’ This enabled the farmers to conserve soil and water on the slopes and begin work straight away to reclaim and rehabilitate the land.

![]() Picture gallery: Farmers systematically share their experience with new farming methods.

Picture gallery: Farmers systematically share their experience with new farming methods.

The region’s fruit trees provide another success story. Once a week, the villagers would take their harvest to the marketplace six kilometres away. But news of the valley’s improved crop yields travelled fast. Today, the buyers come in trucks to purchase fruit straight from the fields. In some regions, these changes have led to an increase in yield of up to 85 per cent and a significant rise in income for farmers.

The farmers received comprehensive instruction prior to planting the fruit trees. The proposal to place a ban on free grazing – at first considered so controversial – is now making a major contribution to the success of the measure, since cattle can no longer destroy the young saplings.

Terracing and water storage systems

Ethiopia has a highly diverse geography. Each region faces different individual challenges. In some places, the need is for water storage systems and terracing, while in others, the planting of specific varieties of trees may bring about the required changes. For this reason, the programme offers farmers a whole range of possibilities to improve their farming methods and increase yields and income.

‘The effectiveness of the programme can be measured by its broad-scale implementation,’ says Johannes Schoeneberger from GIZ, summarising the programme’s success. Over 194,000 households – that is to say around one million people – have successfully implemented the programme’s improved methods on their land. As a result, 180,000 hectares have been rehabilitated and stabilised.

Aberehech Tesfay was one of the first from the village of Alage in the Tigray region to participate in the sustainable land management programme. People in the villages around Alage have been suffering the effects of a severe drought. But thanks to the programme, the 35-year-old has felt little of the impact. On the half a hectare of land she owns with her husband, they have been able to grow adequate supplies of wheat and teff.

Courses on keeping chickens and laying hens

Tesfay and her husband, who together have eight children, struggled for years to cultivate the land. The training course offered by the programme took her to another village 150 kilometres away, where the successes of other farmers were already tangible. Tesfay remembers seeing the photos and being reduced almost to tears: ‘When I saw their fields, I wanted my village to be as green as theirs.’

Exchanges of experience like these have proved the best way of encouraging farmers. Dialogue increases the readiness to try out new techniques. At the training centre near Alage, which is also run by the programme, the courses cover a wide range of topics. Tesfay says that the most useful one for her was a course on keeping chickens and laying hens. ‘I used to have just two or three chickens,’ Tesfay explains. ‘Today I have 50 chickens and three dairy cows.’ She has also bought two goats and says her life has changed dramatically. ‘Before we were surviving on a day-to-day basis.’

Aberehech Tesfay cannot wait to take her farmland and livestock production to the next level.

Contact: Johannes Schoeneberger > hans.schoeneberger@giz.de

published in akzente 1/16

FOR BETTER SOILS

Project: Sustainable land management

Country: Ethiopia

Commissioned by: German federal ministry for economic cooperation and development

National Partners: Ethiopian ministry of agriculture

Term: 2015 to 2017