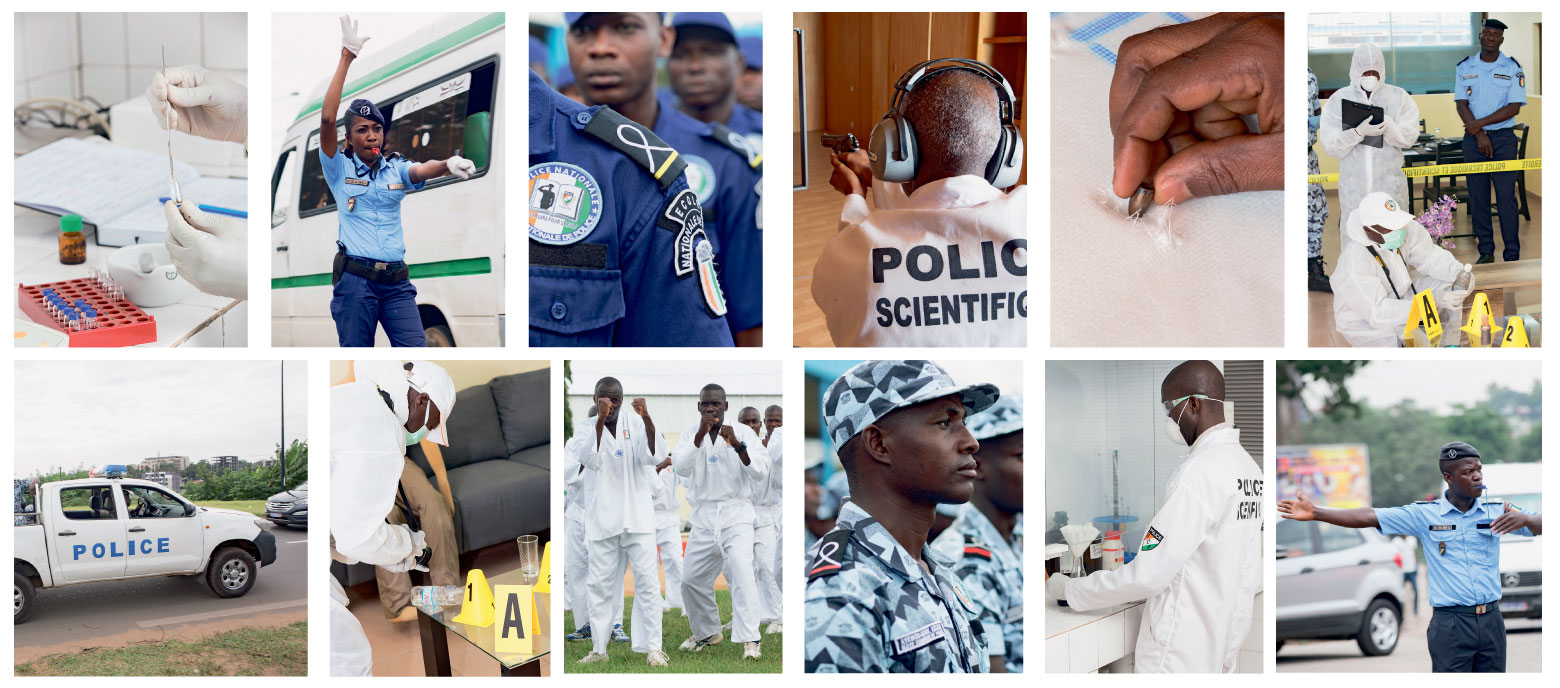

Police Programme Africa

On the right track

‘It happened in our old office. We came to work one morning and noticed immediately at the door that there must have been a break-in. Numerous expensive items of equipment were missing. And the security guard was nowhere to be seen. So, we called the police and the investigators came straight away to begin their work. The forensic officers started by taking fingerprints from all the staff – a good and professional move – before securing further evidence. The investigators also questioned all the staff, myself included.

‘The theft at our company was cleared up quickly.’

The security guard’s absence quickly made him the suspect, and so the police drove to his home – and their suspicions were confirmed. It was subsequently found that he had committed the crime with friends. He has since been tried and sentenced before a court.

We can’t thank the police enough for their swift and earnest action in this case. This allowed the culprit to be caught quickly and the stolen items recovered. While a couple of things are still missing, we got most of them back, as there were only three days between the break-in and the case being solved. We were more than satisfied with the outcome. The police don’t generally enjoy a good reputation in Côte d’Ivoire. They are accused of working negligently and carelessly. Based on this incident, we now have a different impression: the police here are efficient and professional.’ —

‘The training really opened my eyes.’

‘It was during my time at the police college that I first came into contact with forensics. I decided afterwards that this was the field I definitely wanted to work in – it is a new area that could prove extremely helpful to the police force in Côte d’Ivoire. I was given a job in forensics in 2009. Shortly after joining, we attended training run by GIZ in which we learned how to investigate a crime scene. What exactly should you do when you arrive at the scene? How do you take fingerprints and how are they then analysed? The training really opened my eyes. I had just finished my initial training at that time and was unfamiliar with all of this. Of course, I had seen a few things on television and read about forensics in leaflets. But the reality is completely different.

Now, when we arrive at the scene of a crime, the first thing we do is to look for fingerprints. This had also been done in the past, but now we analyse and evaluate them properly. They are an extremely important means of finding out the truth. These methods enable us to work far more scientifically than before, when the focus was solely on questioning.

I have since begun to instruct others myself. We have now trained almost 300 colleagues in cooperation with GIZ. The national police college offers additional courses in forensics. 2015 saw us train some 100 police officers, who are currently deployed all over the country. Overall, police officers are now working at a very high level.’ —

‘Our work also allows us to prove people’s innocence.’

‘When we first started talking about the forensics laboratory here, this was a major discovery for me. In the past, evidence collection meant gathering witness statements and virtually nothing else. We can now follow leads at crime scenes better and piece them together. This all helps to establish the truth and makes our work far more credible. The quality of our evidence gathering has significantly improved.

The laboratory has taken on two tasks in the fight against terrorism. It supports the evidence collection process in this context too, but also plays a preventative role. When we suspect someone of a crime, for example, we can consult a fingerprint database. We can then carry out surveillance on any individual already registered as a suspected terrorist.

At the same time, our work is important in proving suspects’ innocence. There was recently an incident at Abidjan airport where a French traveller was arrested for carrying a liquid on his person, supposedly heroin. But this suspicion proved to be unfounded following our analysis. This example shows how our work can clear someone of the suspicion of drug dealing – and this has not been the only case.

We therefore have further plans for the forensics laboratory. We are hoping that it will obtain accreditation in 2018, as this would boost credibility even further. Finally, I hope that we will have enough finance for the laboratory to become self-funding.’ —

POLICE PROGRAMME IN AFRICA

In many African countries, the public has very little confidence in the police service. Officers are not well trained and there is a shortage of materials and equipment. Investigations often come to nothing, and when cases do go to court, there is frequently a lack of solid evidence. Cross-border cooperation in West Africa is also hampered by insufficient professionalism.

With a view to changing this situation, GIZ has been working on behalf of the German Federal Foreign Office since 2009 to support police reforms in several African countries. The focus is on better training and equipment. The programme is currently supporting police work in Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Niger and Nigeria. Regional organisations such as the African Union, the Economic Community of West African States, the Eastern Africa Standby Force and the G5 Sahel initiative are also involved in these cooperation activities. The goal is to modernise police work in line with international standards..

The forensics laboratory in Abidjan shows what this cooperation can be like in practice. The facility allows testing of drug samples, as well as weapons, projectiles and counterfeit money. This makes it possible to reconstruct crimes that would otherwise have remained shrouded in mystery forever. —

Contact: Marina Mdaihli, marina.mdaihli@giz.de

You can find an interview with Marina Mdaihli here.

THE PROJECT IN FIGURES

16,000 police officers

have been trained since 2016 alone.

23 forensic facilities

have been equipped, including a large forensics laboratory.

published in akzente 3/18