Refugees in Jordan

Precious water, new opportunities

Asia Khaled Salamed fled Homs in 2011. Maryam Ahmad Hariri left Damascus two years later. Shatha Ahmad turned her back on her war-torn home in 2014. Fatima Ahmad Mubarak from Daraa in southwest Syria decided in 2015 that leaving her home was her only option. Today, these four women live as refugees in Jordan. As they stand together in the classrooms at the Hakam vocational school in Irbid, one of the country’s three largest cities some 70 kilometres north of the capital Amman, they seem remarkably cheerful. Dressed in grey overalls, they report on the terrible events back home. But they also talk of their new, positive experiences at the vocational school.

Here it is all about hands-on learning. Asia Khaled Salamed, 39 years old, and Fatima Ahmad Mubarak, three years her junior, lift a washbasin on its side. Maryam Ahmad Hariri, 34, and Shatha Ahmad, 24, unscrew the fixing ring holding the mixer tap.

All belongings destroyed in the war

Brigitte Schlichting watches their work with a stern yet benevolent eye. ‘That’s good,’ she says and nods approvingly at the four Syrian women. Khaled Salamed smiles. In their former lives the four women were a seamstress, a hairdresser, a housewife and a student. Each is a mother to several children. All four fled the country, with or without their husband, as the situation dictated. They abandoned their homes and their belongings – if these had not already been destroyed in the war.

Now these four stand alongside 11 other Syrian women and 14 women from Jordan at the vocational school’s long workbenches. Schlichting is their teacher, a 53-year-old master plumber from Berlin. Her job is to pass on her passion for the job of sabaka or plumber. She has been working as one herself for more than 30 years and has her own plumbing business in Berlin.

New hope after the hazardous escape

Khaled Salamed also wants to become a plumber and – as soon as she is able to return to Syria – use her skills to help rebuild the destroyed city of Homs. ‘Just like the Trümmerfrauen who helped rebuild Germany out of the rubble of the Second World War,’ she says, as she continues work on a fitting. ‘And I intend to work for myself, I want to be independent of a husband’s income,’ adds Fatima Ahmad Mubarak. None of the four women considered migrating to Europe as an option. Jordan is close to their home, the culture is similar – and they all want to return as soon as possible when the war is over.

A small, energetic woman, Khaled Salamed is already putting into practice the skills she has learned in the course. By helping out friends and relatives, she is able to supplement the 20 dinars (equivalent to around EUR 25) the refugees in Jordan receive per month from aid organisations. Officially they are not allowed to do other work. After her hazardous escape from Homs by car, on foot and by bus, Khaled Salamed found a small apartment in Irbid. She has been living there with her six children since 2011. Today she thinks nothing of dismantling a tap or fixing leaks in the pipes at home. And she even has the confidence to tackle other jobs around the apartment. ‘When the fluorescent light stopped working, I took it apart. The contacts had worked loose – it wasn’t a problem.’

Tackling the problem of water shortage

The plumbing course is just one of the projects run by GIZ in Jordan. It has two objectives: to provide refugees with career prospects, and in addition help tackle one of the country’s most pressing problems – a shortage of water. Jordan is one of the most arid countries on earth. According to German expert Daniel Busche, 40 per cent of the water is lost as a result of leaking taps and dilapidated pipes. The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) currently supports plumbing courses for approximately 300 women and men, 40 per cent of them Syrian refugees. At the end of the course, each participant receives a box of tools to enable them to set up their own business or form a cooperative.

![]() Picture gallery: Syrian and Jordanian women are learning to be plumbers.

Picture gallery: Syrian and Jordanian women are learning to be plumbers.

Their role model is Brigitte Schlichting. She comes to Irbid for a few weeks two or three times a year. She motivates the women, builds their self-confidence and strengthens their role in the male-dominated, Islamic society. Initially the men scoffed at the idea of plumbing courses for women, explains Shatha Ahmad. ‘They thought the work was too physical for us.’ She and the others disagreed. In the meantime they have earned the respect of the men. ‘Quite a lot of them have two left hands and do more harm than good when it comes to repairing things,’ says Fatima Ahmad Mubarak with a smile.

Population growth as a result of the refugee crisis

Another person who has enormous respect for the women in Irbid is Hazim El-Naser. As Minister of Water and Irrigation, he holds one of the key posts in the Jordanian Government. In Jordan, the average amount of water available for each individual per year is 100 cubic metres. The amount in Germany is around 20 times higher. Eighty per cent of Jordan’s land area is desert. ‘The volume of refugees from Syria has exacerbated the problem considerably,’ explains El-Naser. ‘Demand for water suddenly went up by a quarter. And in the north, close to the border, where most of the Syrians have ended up, it has almost doubled.’ The groundwater level is dropping by a metre a year on average, sometimes by as much as five metres. Everyone, Jordanians included, is having to ration their use of water.

In Mafraq, for example, a city in the north of the country, the population has doubled to around 200,000 as a result of the refugee crisis. Some claim the figure is three times what it was. Ten kilometres east of Mafraq, around 80,000 people currently live in the Zaatari refugee camp, a site covering an area the size of 750 football pitches. Only by making urgent appeals to the population, raising prices and destroying 800 illegal farmers’ wells have the authorities been able to prevent the water supply from total collapse, the Minister explains.

Imams and Muslim counsellors as ‘water ambassadors’

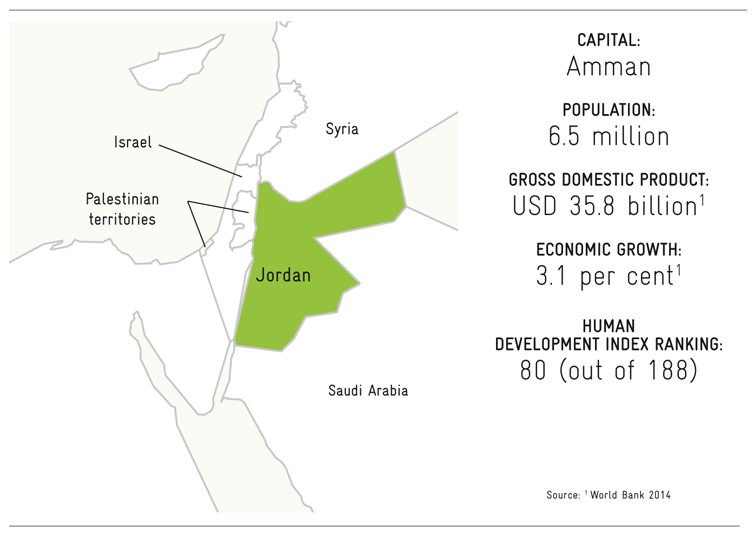

But El-Naser knows that this is not enough – particularly as it is impossible to predict how long the 640,000 refugees will stay in Jordan, which itself has a population of just 6.5 million. So every opportunity to save water is being exploited. Imams and Muslim counsellors are being given information on ways to save water and their mosques are being equipped with new plumbing. Each year in Amman alone, 500 million litres of water are used for ritual washing before prayer and to clean the mosques. The goal is to reduce this by a third. During prayer, Khaled Al Khatib, the imam at the Usama Ibn Zaid mosque in Mafraq, refers to the importance of using water sparingly, and quotes relevant verses from the Koran. In the training courses, he and the other imams also learn about rainwater collection systems and about recycling grey water for agricultural or industrial use. ‘Over 90 per cent of Jordanians and Syrians attend a mosque,’ says German expert Björn Zimprich. So the imams and Muslim counsellors are important multipliers. The project has already trained 800 of them to become ‘water ambassadors’ since 2015, with almost one thousand more to follow.

Meanwhile, there is plenty of work to be done in households and apartments across Jordan for Brigitte Schlichting’s trainee band of female plumbers. But the women have one major advantage over their male counterparts: female plumbers can carry out repairs even when only women are in the house. According to Islamic understanding, a male plumber can work in the building only when the master of the house is present. And are women allowed to work on plumbing installations at the mosque, too? Imam Al Khatib nods. ‘Of course,’ he says. But his expression betrays the fact that this is nothing short of a minor revolution. The 56-year-old cleric with friendly eyes and a full black beard explains the one caveat: it can only happen provided no men are attending the mosque. But that is not a problem for the women on the current course, he says. Nor, one assumes, for the 100 or more whose names are on the waiting list for the next.

Contact: Thomas Schneider > thomas.schneider1@giz.de

published in akzente 2/16

PROS IN DEMAND

Project: Support for jordanian communities in response to the syrian refugee crisis through water wise plumbers (wwp)

Country: Jordan

Commissioned by: German federal ministry for economic cooperation and development

Lead executing agency: Jordanian ministry of water and irrigation (mwi)

Term: 2014 to 2016